Another water war: The story of the Attica-Covington Skirmish

How another battle over water and commerce in the 19th century led to two Fountain County communities to come to blows.

Thanks today for ongoing help from Based in Lafayette sponsor Long Center for the Performing Arts. Tickets to upcoming shows make a perfect gift. For tickets, details and more on these shows, go to longpac.org.

Editor’s note: As communities up and down the Wabash River push back against a proposal to pump water from the aquifer western Tippecanoe County to huge industrial developments two counties away, let’s remember this wasn’t Indiana’s first water war, pitting one community against another. Today, Kevin Cullen, a former J&C reporter who always had the right touch when telling the region’s history, recounts a 19th century battle – as in actual bloodshed – between two Fountain County cities over slow to make its way along the Wabash & Erie Canal. They called it the Attica-Covington Skirmish.

ANOTHER WATER WAR: THE STORY OF THE ATTICA-COVINGTON SKIRMISH

By Kevin Cullen / For Based in Lafayette

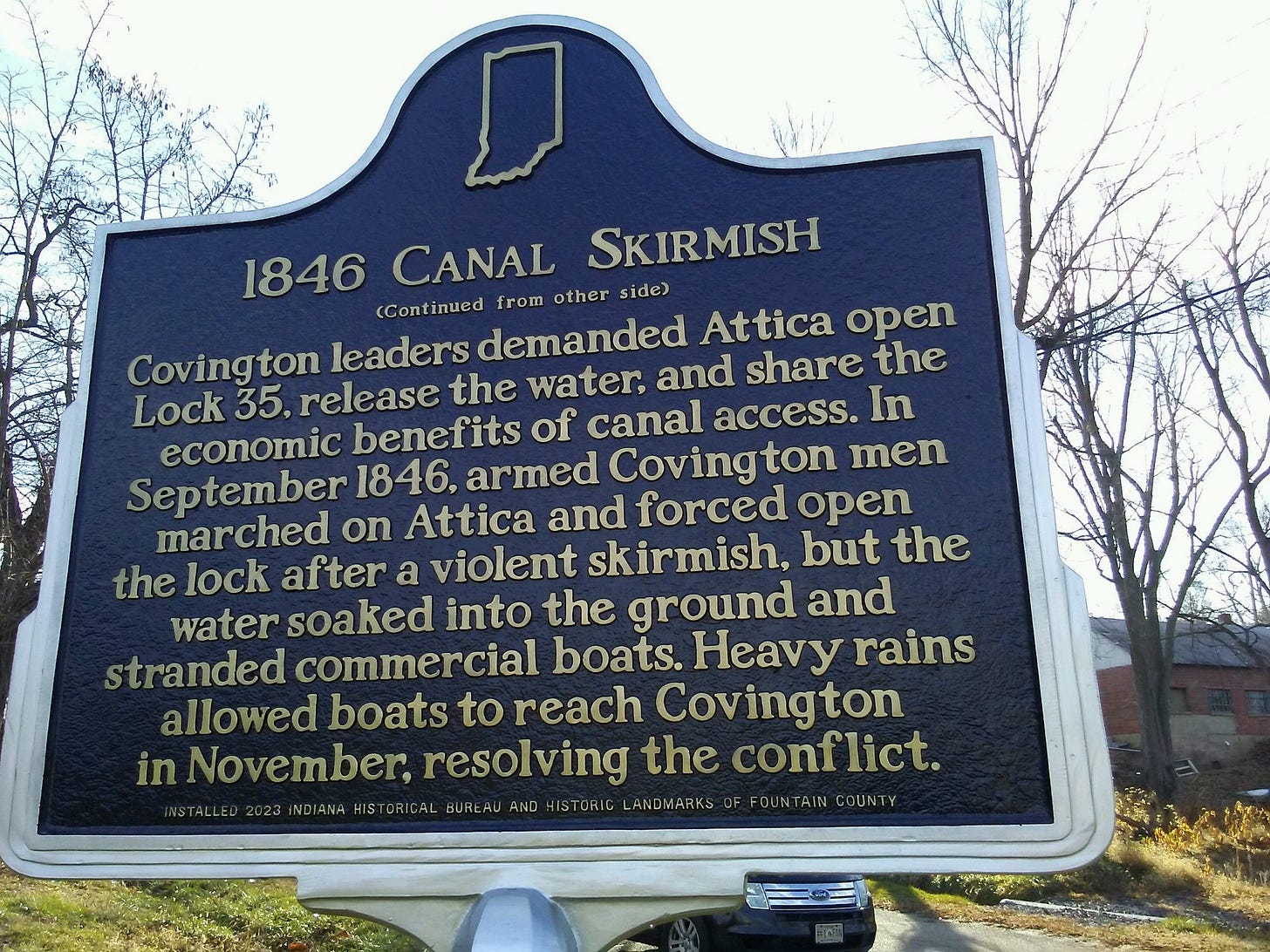

ATTICA – Between the river and the drive-thru at McDonald’s lies a grassy ditch that once was part of the busy Wabash & Erie Canal. Beside it is a sign that tells the story of a vigilante-style assault and brawl over water rights, fought in 1846.

The incident known as the “Attica-Covington Skirmish” or the “Attica War” centered on wooden-framed Lock 35, which stood at that very spot. Even today, the attack by 300 angry Covingtonians, and their bloody free-for-all with Atticans, form a popular chapter in Fountain County history.

County historian Carol Freese says that even today, 177 years later, the melee is misunderstood.

“It is of interest because of the details, the facts and the repercussions,” said Freese, a Covington antiques dealer and civic leader. “People like to hear about it, and it always sparks some laughter. It even seems absurd by today’s standards, but in reality it must have been very serious to the locals in Covington who relied upon the canal for commerce.”

The 468-mile-long Wabash & Erie, dug largely by Irish immigrants, linked Lake Erie to the Ohio River. In its day, it was the longest U.S. canal and a remarkable engineering achievement. It carried both passengers and freight, allowing Wabash Valley farmers to cheaply move pork and produce to Eastern markets, and for Eastern merchants to cheaply ship everything from plows to pianos to the West. A necklace of communities from Toledo to Evansville – including Lafayette, Attica and Covington – became booming, bustling canal towns.

Controversies over water control continue, of course. In 1846, Covingtonians physically battled their Attica neighbors to try to get water to their docks. Today, cities and counties all along the Wabash River are fighting a plan to pipe up to 100 million gallons of water daily to a proposed high-tech development site near water-poor Lebanon.

Bad blood had existed between Covington and Attica for years. Both towns were on the Wabash. Attica was larger, but Covington – 14 miles to the south – captured the coveted county seat. Resentment, jealousy and rash judgments flourished.

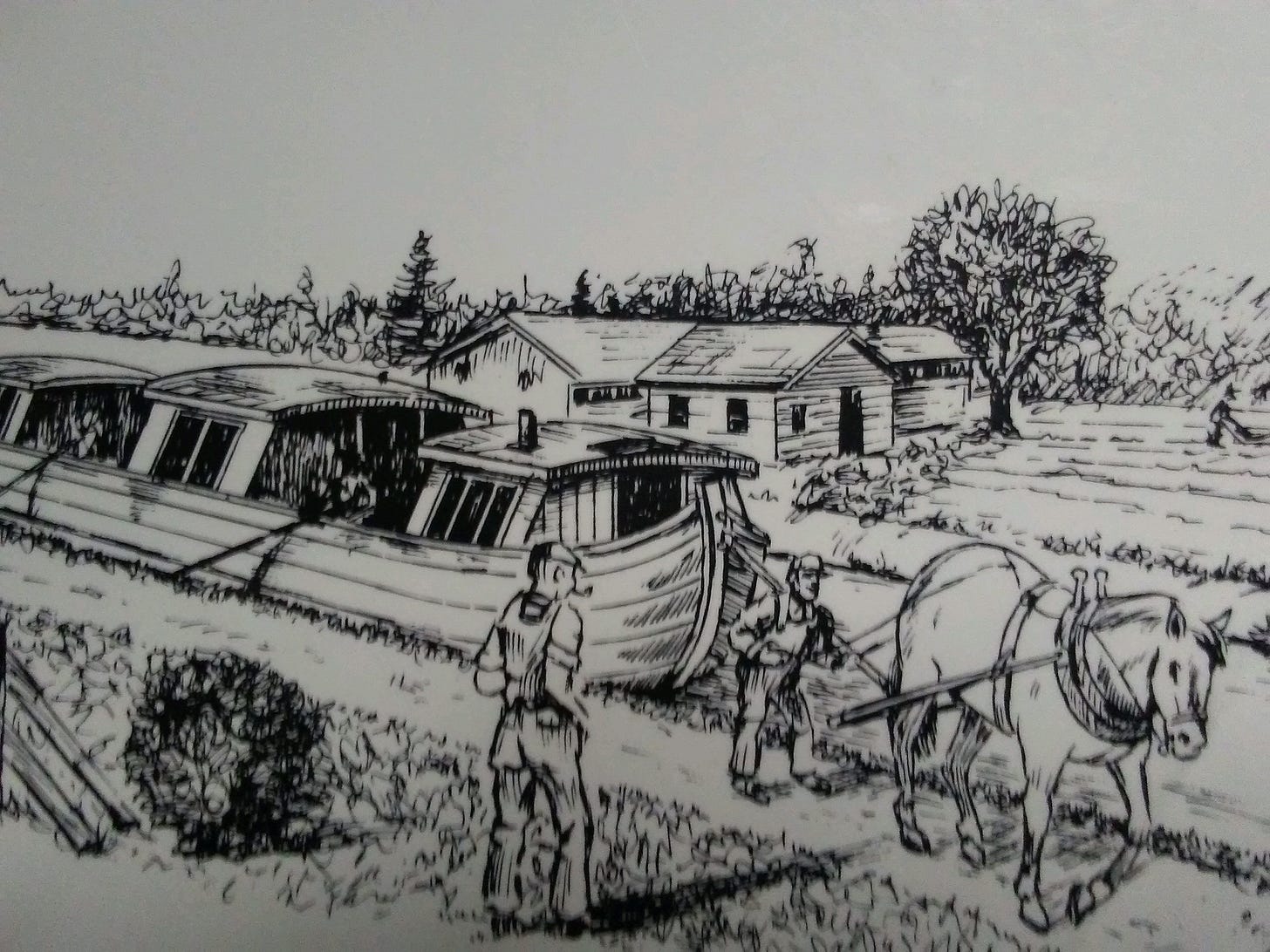

Canal construction began in 1832. Locks were built to raise and lower canal boats through grade changes; horses and mules, plodding along the towpath, towed the boats with ropes. Water came from rivers, creeks and streams, and was stored and released via feeder dams.

Looking for more local stories heading into 2024? Consider a subscription to the Based in Lafayette reporting project. Free and full-ride options are available here.

By 1846, the canal had been extended to Attica and Covington. Both towns itched to reap the rewards that came from canal traffic. At a time of deplorable roads, only waterways offered affordable, long-distance transportation.

“The completion of the canal to Covington will undoubtedly, materially increase the revenues to be derived from that source and afford a northern outlet to one of the most fertile regions in Indiana,” the canal superintendent wrote in an 1846 report to the Indiana General Assembly.

“They have looked upon the completion of this work as an epoch in the history of that county, and it is not the least surprising that they should feel, and manifest too, much anxiety on the subject.”

But disappointment, in big chunks, descended when drought hit. Little rain fell for three months. Feeder streams and creeks dried up. The waterway was navigable from Attica north. But Lock 35 was kept closed, which kept water from reaching Covington.

Armed Attica citizens booted canal personnel aside to keep the lock closed, Henry Sinclair Drago wrote in “Canal Days in America.”

“Sourly contemplating a dry ditch week after week, Covingtonians began to simmer with mounting ire,” Purdue English professor Paul Fatout wrote in his 1972 book, “Indiana Canals.” “They convened in indignation meetings, made stirring speeches, adopted salty resolutions and forwarded sharp protests to the canal superintendent.

“Still getting no water, they concluded that selfish persons at the Attica lock were deliberately shutting off the flow. Then Covington went on the warpath.”

An often-quoted account was written by Lucas Nebeker for the March 1913 edition of “The Indiana Quarterly Magazine of History.” Nebeker had interviewed several participants many years before.

“The section above Attica, being previously constructed, had become filled and an immense business was being done on the canal, with Attica as the western terminus for the time being, and that town was in the enjoyment of prosperity never dreamed of before,” Nebeker wrote.

Enter U.S. Sen. Edward A. Hannegan, who was back home in Covington. Known for his fiery, persuasive oratory, he became the lightning rod that attracted followers and fueled their already-flaming passions. (Hannegan later was accused of killing a man with a dagger. He died of a morphine overdose in 1859.)

“Townspeople jumped on the bandwagon and followed him,” Freese said. “He was known to be too fond of liquor and for all we know this was what spurred him on as well as the accolades he received … ”

Hannegan first assembled several leading citizens, headed to Attica and asked the locals to open Lock 35. No dice.

Returning to Covington, his troops angrily fired a cannon to attract a crowd. Quickly, a hostile takeover was planned. On Sept. 26, 1846, Hannegan led 300 vigilantes north on River Road toward Attica. Some were on horseback, some were on foot. Many carried clubs, some toted firearms.

“The threat from Attica was not to be tolerated,” Freese said. “These men were frontiersmen who were used to fighting and working for improving their lifestyles.”

“It appears the patience and forbearance of the citizens of Covington have been completely exhausted,” wrote The Delphi Carroll Express, “and they have resolved to redress their grievances in their own way.”

“The band of ruffians was headed by E.A. Hannegan, U.S. senator from Indiana,” The Logansport Telegraph reported, “who gave orders with all the pomp of a Bonaparte. His actions throughout are condemned by everyone in the region.”

“The whole affair,” wrote The Fort Wayne Times and People’s Press, “was a very disgraceful one, and one in which an honorable senator ought not to have been found.”

Hannegan’s ragtag army was spotted and an alarm was received in Attica. A wagon loaded with armed men headed south from there, hoping to stop the assault. Attica businesses closed, and a crowd assembled to defend precious Lock 35.

The Covingtonians quickly disarmed and captured their opponents on the road and continued north toward the lock. The war – more skirmish than war – featured shouting, punching and clubbing. Blood was shed, but no one was shot, killed or maimed. Ezekiel M. “Zeke” McDonald, a leader of the Attica forces, was clubbed and pitched into the canal.

“The mob cried, ‘Kill him. Drown him,’ which they came very near doing,” The Logansport Telegraph reported. “Three or four others were struck but not as much injured.”

Triumphant, the Covingtonians forced the lock open, allowing water to surge into the dry, gravelly channel. Within 30 minutes, the water-filled section was almost drained; below the lock, water was soon absorbed into the parched earth. Thirty canal boats, filled with cargo, were stranded, tilted on their sides, stuck in the muck.

The damaged lock would not close. Attica folks dumped tons of hay into the canal bed to try to form a makeshift dam, but the water still seeped through.

“The real losers were the boats that had been caught in the lock,” Drago wrote. “As the water fell, they sank into the mud and remained there for weeks.”

The Attica Journal called the Covington men ignorant and lawless, and added that Attica wanted nothing more to do with them. Editor Enos Cannutt hissed that “the very air they breathed was contaminating and odious to Attica.”

Solon Turman, editor of The People’s Friend in Covington, counterpunched: “To be banished from the presence and society of Enos Cannutt, Esq., proprietor, editor and (printer’s) devil, all himself of The Attica Journal, was indeed a heavy blow.

“Whether or not Covington would be able to survive this terrible deprivation was an unsolved problem whose answer was concealed in the mists of futurity.”

Anger remained, but the crisis passed when heavy rains came, recharging the river and feeder streams. The first canal boat reached the Covington docks on Nov. 30.

It “arrived at Covington Monday of last week,” The Delphi Carroll Express reported on Dec. 5, 1846. “Great demonstrations of public joy were had on that occasion. It will form a new era in their commercial history of which they may well be proud.”

The Wabash & Erie Canal was completed in 1853 when it reached the Ohio River at Evansville. But by then railroads were making it obsolete. Railroad lines were cheaper to build and maintain. Trains were faster, and they didn’t stop when water froze or a drought hit.

The canal closed for good in 1875.

Looking back in 1913, Nebeker remembered the conversations he had had with old-timers who once fought over Lock 35.

“Viewed from the standpoint of the present, (it) seems like a farce,” he wrote. “But 50 years ago, it was talked about seriously as the ‘Attica War’ and to those who participated, it was never a joke.”

FOR MORE

Holcomb, Statehouse leaders try to assure Greater Lafayette on LEAP pipeline

Second well test done for LEAP pipeline; Granville neighbors fight being an ‘afterthought’

Thanks, again, for ongoing help from Based in Lafayette sponsor Long Center for the Performing Arts. For tickets to upcoming shows, go to longpac.org.

Thank you for supporting Based in Lafayette, an independent, local reporting project.

Tips, story ideas? I’m at davebangert1@gmail.com.

What a great piece of local history. It's a shame that no local band has (as far as I can tell) used the name "Lock 35".

Canal building nearly bankrupted Indiana including the 1836 Indiana Mammoth Internal Improvement Act that paid for the canal section described in this story. A land survey (not done) would have shown it was doomed from the start. Something to recall before building a $2 billion Straw to Nowhere.