Operation Babylift crash survivors help dedicate marker for Vietnam War hero Mary Klinker

Retired Capt. Regina Aune and Aryn Lockhart tell the story of the doomed flight in 1975, in the closing days of the Vietnam War, that killed Air Force nurse and Central Catholic grad Mary Klinker

Support today comes from Purdue’s Office of Diversity, Inclusion and Belonging, presenting a free showing of “The Price of Progress: The Indiana Avenue Story” on Nov. 14 at Stewart Center’s Fowler Hall. The two-act play highlights the heritage of a downtown Indianapolis community called “The Harlem of the Midwest” for its thriving culture of Black-owned businesses, performing arts, educational influences and a jazz legacy — from bebop to hip-hop — that attracted the most renowned musicians of the 20th century. Get more details and free tickets here.

Editor’s note: Today, Based in Lafayette correspondent Angie Klink brings a Veterans Day story from last week’s dedication of a historic marker honoring Mary T. Klinker, on the grounds of Central Catholic High School.

NURSE, ORPHAN ABOARD OPERATION BABYLIFT CRASH HELP DEDICATE MARKER FOR HERO MARY KLINKER

By Angie Klink / For Based in Lafayette

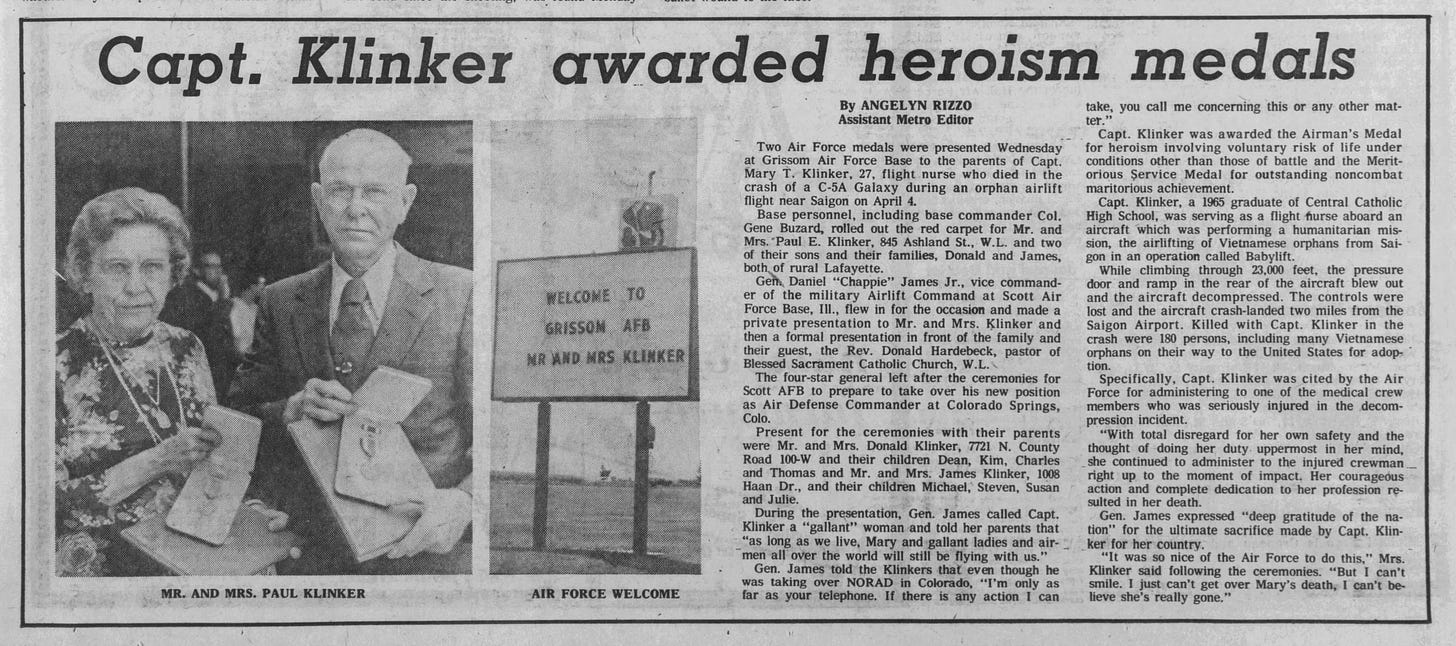

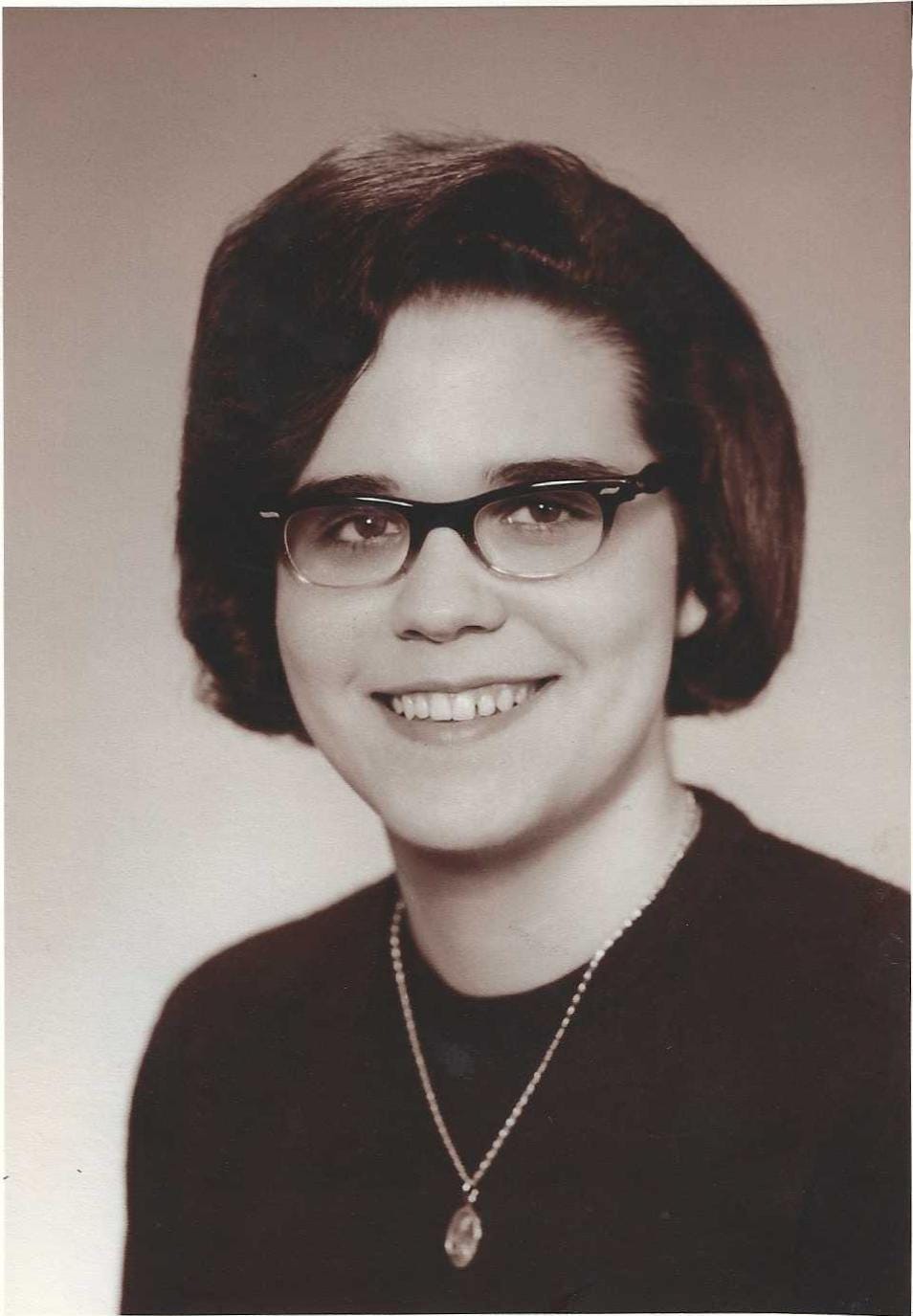

At the last minute U. S. Air Force Capt. Mary Therese Klinker became one of the nurses assigned to the ill-fated inaugural flight of Operation Babylift on April 4, 1975. Born and raised in Lafayette, Klinker was the raven-haired, bespectacled 27-year-old daughter of Paul and Mary Klinker who graduated from Central Catholic High School and St. Elizabeth School of Nursing. She became the last nurse and the only member of the Air Force Nurse Corps to be killed in the Vietnam War. She is one of only eight women among more than 58,000 with their names on the Vietnam Memorial Wall in Washington D.C.

Wearing her Air Force blue utility slacks and shirt, Klinker boarded the enormous C-5A Galaxy, one of the largest planes in the world, where she could hear the cries and coos of about 200 South Vietnamese orphans under the age of 2, holding bottles, swaddled in blankets, propped with pillows and tethered with seatbelts. They were headed to Clark Air Force Base from Saigon, and ultimately to the United States, Australia, Canada and Europe where they would be adopted as the Vietnam War came to a close. However, soon after takeoff, the plane crashed, killing 138 of the 300 people on board, including Klinker.

Last week, the General de Lafayette Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution hosted its annual Veterans Day luncheon, honoring Klinker by featuring speakers Col. (Ret.) Regina Aune, a nurse who was the Medical Crew Director on the devastating flight, and Aryn Lockhart, one of the Vietnamese babies on board. The two women connected in 1997, formed a bond over the years and co-authored their 2014 memoir “Operation Babylift: Mission Accomplished, a Memoir of Hope and Healing.”

During the collapse of South Vietnam, President Gerald Ford ordered the evacuation of Vietnamese orphans from Saigon and the mission was officially named Operation Babylift. Many of the babies were fathered by U.S. military men. More than 3,000 orphans were evacuated within a month’s time.

Col. (Ret.) Regina C. Aune, Air Force Nurse

“April 4, 1975, was the worst day of my life,” Col. Aune said to the DAR luncheon guests last week. Aune and Mary Klinker were both flight nurses with the 10th Aeromedical Evacuation Squadron out of Travis Air Force Base in California.

“Mary and I had flown to Clark Air Force Base on Easter Sunday,” Aune said.

Aune and her medical crew waited on the plane having no idea what their mission was until the colonel boarded and told them they would be responsible for 200 babies and their caregivers. Aune, 31 at the time, had only been in the Air Force for two years and had less than one year of flight experience.

At that point Klinker was assigned to a different plane. Because they had not flown in a C-5 before, Aune and her team were briefed on the location of the aircraft’s emergency equipment. Aune introduced her crew to the pilot, Capt. Dennis “Bud” Traynor, and he said. “I’ve never flown an air vac mission in my life. What do I do?” Aune said, “Just fly the plane.”

He would soon struggle to crash land the plane.

The crew and caregivers formed a bucket-brigade to load the babies up the stairs and into the plane in Saigon. The air was thick with emotion, as young Vietnamese women, nuns and other caregivers tearfully handed over children they had loved and cared for in an orphanage and would likely never see again.

“As I took each child from the arms of each anguished woman, I too wanted to cry,” Aune wrote in her book. “Their pain was palpable, and I wished there was some way to ease it and assure them I would care for these children with all the tenderness and concern that they had for them.”

The C-5 had two floors. Above the cargo area is the troop compartment with seats facing the rear of the plane. Most of the younger children went there, but a few were down below in the cargo section. There were three seats in tandem, similar to a commercial airline. The armrests were removed, and six babies were placed across the seats, harnessed by seat belts.

After the children were secured, Klinker came to the plane and told Aune that her crew was told to augment Aune’s crew. Aune assigned Klinker to stay downstairs with her in the cargo level.

“Mary and I were in the same squadron, so we knew each other,” Aune said. “She was actually my rater for performance reports.”

The plane took off and a few moments later as it climbed to 23,000 feet, one of the caregivers in the cargo area became violently ill. Aune, Klinker and one of the med techs from their squadron left their seats to care for her. Then Aune ran upstairs to the troop compartment to retrieve medication, an action that would save her life.

While she was kneeling on the floor grate reaching for the medication, there was an abrupt, deafening boom and immediate rapid decompression. The plane filled with a mist and began to plummet. Insulation and debris flew through the air. People were screaming, babies were crying.

Aune would learn later that the massive rear cargo door blew off, creating a huge gaping hole in the rear of the aircraft. It would be deduced that the locking mechanism on one of the doors failed.

“When I looked down after everything cleared, I saw that the back end of the plane was gone and hydraulic fluid was spewing everywhere,” Aune said. “I (also) saw the South China Sea, and thought I’m not supposed to see the South China Sea from here. It was beautiful, but also terrifying.”

Aune quickly moved into safety procedure mode. She had no idea what was happening down in the cargo area she had just left. She found out later that the med tech helping the sick caregiver had been knocked unconscious, and Klinker was caring for him.

“Because when they found their bodies, they were right together,” Aune said. “Mary took care of him until the crash landing.”

Pilot Traynor got the plane turned around to return to Saigon, aimed for the runway, and touched ground on one side of the Saigon River. Then the plane went airborne again and jumped the river.

“When we hit the first time, the escape slides in the troop compartment began to inflate,” Aune said. “Sgt. Parker, a loadmaster, slit them with his pocketknife so they would not suffocate everyone.”

It was his last heroic act. When the aircraft went airborne before hitting ground the second time, Parker slammed into the troop deck wall, went through it and was killed.

Like a speedboat, the plane shot across the water, a river of mud surrounded by rice paddies. Sitting on the floor, Aune slid rapidly to the other end of the troop compartment and smashed into the wall, feet first, breaking all of the bones in her right foot. The cargo compartment below where Klinker was tending to her colleague was sheared off, killing them both.

The plane broke into its component parts with the passenger section largely intact. Black smoke from burning fuel billowed in the hot, humid air as evacuation began. The entire flight from takeoff to crash landing had occurred in 15 minutes. Traynor and his crew survived.

Rescue helicopters soon arrived. The adults, including Aune who soldiered on with a broken foot – she would learn later that she also had a broken leg and vertebra in her back – grabbed babies, two and three at a time, and walked backwards in knee-high mud against the debris shooting up from the whirling blades of the helicopters.

“One little boy had gotten out and was crawling over the opening where there were jagged pieces of the plane,” Aune recalled. “And I thought, He’s going to drown in the mud. So I leaned over and grabbed him by the seat of his pants, the only way I could pick him up. And when I went to stand, I couldn’t.”

Aune has no recollection of what happened next. She was told later that she walked over to the navigator and said, “Major Wallace, I need to be relieved of duty because my injuries prevent me from continuing.” Then she promptly fainted. The next thing she knew, she opened her eyes, and he was carrying her and the baby to the rescue helicopter. In 1976, Aune became the first woman to receive the Cheney Award, recognizing an act of valor, extreme fortitude or self-sacrifice in a humanitarian mission connected with aircraft.

None of the children downstairs in the cargo compartment survived. The only baby who died upstairs was thrown out of a forward-facing loadmaster seat. Babies in rear-facing seats survived. One of those babies was Aryn Lockhart.

Aryn Lockhart, Orphan Survivor

Aryn Cristin Lockhart’s American parents had always told her she was one of the adopted orphans of the Operation Babylift disaster. They kept newspapers, articles, letters and photos about the tragic flight to show her. The first time she wrote about her story was in fourth grade when she entered a creative writing competition and took first place.

Lockhart grew up looking at two black-and-white pictures of herself as a baby held by two nuns at the Vinh Long orphanage. In one photo she is in the arms of Sister Mary Agatha “Ursula” Lee who chose her for her adoptive parents. “Sister Ursula died in the plane crash,” Lockhart told the DAR luncheon attendees that included the brothers of Mary Klinker, Don and Jim, and a table of Klinker’s Central Catholic classmates from the class of 1965.

When she graduated from college in 1996 and the Internet was fairly new, Lockhart began to research her backstory. She found an article titled, “The Lady was a Tiger” where she first read of the heroic efforts of Regina Aune. With a mix of desire to know more and fear of rejection, she mustered the courage to contact Aune.

“I expressed my gratitude for the work that she had done to help me have the life that I had,” Lockhart recalled.

Aune told Lockhart that during the bucket brigade to enplane the orphans onto the C-5 Galaxy, Aune would have held Lockhart in her arms.

For years, Aune was asked if she had been in contact with any of the orphans, but there was no way she could as she had no names or means to track them down. Eventually, as the babies came of age they began reaching out to connect. Lockhart was one of the more ardent seekers of her past.

Over the years, Aune and Lockhart became close, and Lockhart now refers to Aune, who lived in San Antonio, as “SA Mom.” In 2014, the 40th anniversary of Operation Babylift, the two, along with Ray Snedegar, a loadmaster who survived the crash, traveled to Vietnam and stood on the field, formerly rice paddies, where the C-5 had crashed.

“It was quiet and it was powerful,” Lockhart said. Veterans Day took place while they were on the two-week trip, and they wanted to return to the field that day with flowers and incense. Working through an interpreter, their driver appeared to be turned around.

“So we ended up in someone’s front yard,” Lockhart said. “Then, come to find out, we were at a shrine.”

The shrine was a small, tan structure, about 4 feet high, with a narrow rectangular opening. It stood on private property where the tail end of the plane landed after the crash. Beneath the shrine rests a part of the rusted wreckage. At the opening of the shrine, Lockhart lit incense to honor Aune and Snedegar as veterans and those who had perished on the C-5. However, there was nothing that explained the significance of the shrine and that troubled Lockhart.

“I knew immediately that I wanted to leave something to tell all who passed by why this shrine was built,” Lockhart wrote in her book.

She designed a collage with a dedication in both English and Vietnamese, a picture of the C-5 Galaxy taking off and an image of the wreckage. Before they left Vietnam, they returned for a final visit to the shrine, placing the dedication collage inside. Lockhart wore the traditional Vietnamese dress, an ao dai, as she did for her talk at the DAR luncheon.

Serendipitously, while in Vietnam, Lockhart needed to make a weekend trip to Malaysia for work. Sister Ursula, who was responsible for Lockhart’s placement with her parents, was from Malaysia, and her body had been returned to her hometown after the crash. Lockhart was able to visit Sister Ursula’s gravesite.

“I placed the flowers in the vase on her gravestone and the moment I looked up and saw her name and her death date, I sobbed,” Lockhart wrote. “As I stood before her, I thanked her. I told her how important she has been my entire life and … how much she is loved and a part of me.”

After the visit to Vietnam, Lockhart began searching for other nuns who were at the orphanage during her time there. She traveled to Taiwan and met the nun holding her in the other photo she grew up staring at and wondering of her past.

“The amazing thing about nuns is that they just do their work, and they do it quietly and they do it with purpose,” Lockhart said. “They don’t do it for accolades.”

Lockhart has visited the Vietnam Memorial in Washington, D.C., several times.

“Within the vast sea of names and the lives lost so tragically, I feel an indescribable connection,” Lockhart wrote. “… my hands have traced over the names of the C-5 crew.”

The photo on the cover of the DAR luncheon program showed Lockhart kneeling at the Vietnam Memorial. By sheer coincidence, her hand on the black granite is next to the name of Mary T. Klinker.

Lockhart posted that same photo on social media on April 4, 2017, the anniversary of the crash of Operation Babylift, and it led to another connection to Klinker.

“I get chills just thinking about this,” Lockhart said. “I got this note that said, ‘I never knew you were part of Operation Babylift. Were you on the plane that crashed? Chuck, who I am dating, his aunt is Mary Klinker who died on it. Wondered if you knew of her. I saw your hand by her name.”

Lockhart went to middle school and played basketball with Erin, now the wife of Chuck Klinker.

“I had always known who Mary Klinker was,” Lockhart said. “But by no means did I know I had a connection.”

Lockhart ended her talk with this: “We have to live by example. When there’s tough times, the question is who are the helpers? Mary Klinker was a helper.”

Capt. Mary T. Klinker Marker Dedication

After the luncheon, DAR held a dedication for a marker honoring Mary T. Klinker at the new Spiritual Plaza at Central Catholic High School on South Ninth Street. The Central Catholic class of 1965 and local veterans contributed funds for the marker’s creation. Text on the plaque states that Klinker was posthumously awarded the Airman’s Medal for Heroism and Meritorious Service.

After a 21-gun salute by the Honor Guard of American Legion Post 492, remarks were made by Lafayette Mayor Tony Roswarski and state Rep. Sheila Klinker, whose husband Vic is a cousin to Mary. Greetings were also given by Regina Aune, Aryn Lockhart and DAR representatives. Don and Jim Klinker, Mary’s brothers, placed a wreath at the foot of the marker.

At the close of the ceremony, Sheila Klinker and Lafayette City Council member Eileen Hession Weiss began an impromptu singalong. The crowd joined in, holding hands, as the words floated over the Spiritual Plaza of “God Bless America.”

Thanks, again, to Purdue’s Office of Diversity, Inclusion and Belonging, presenting a free showing of “The Price of Progress: The Indiana Avenue Story” on Nov. 14 at Stewart Center’s Fowler Hall. Get more details and free tickets here.

THANK YOU FOR SUPPORTING BASED IN LAFAYETTE, AN INDEPENDENT, LOCAL REPORTING PROJECT. FREE AND FULL-RIDE SUBSCRIPTION OPTIONS ARE READY FOR YOU HERE.

Tips, story ideas? I’m at davebangert1@gmail.com.

Thank you, Angie Klink, for writing and sharing this incredible story about these incredible, heroic people. This is must reading for any of us who are old enough to remember those times. And thank you, Dave Bangert, for sharing your journalism talents through your Based In Lafayette substack.

Thank you for this heart wrenching article. She was the best of the best. Wish I had known her.