Q&A: New book tells the story of the Marquis de Lafayette’s tour that inspired this city’s name

Ryan Cole’s new book, ‘The Last Adieu,’ details the national sensation Lafayette set off when the Revolutionary War hero returned and toured the U.S.

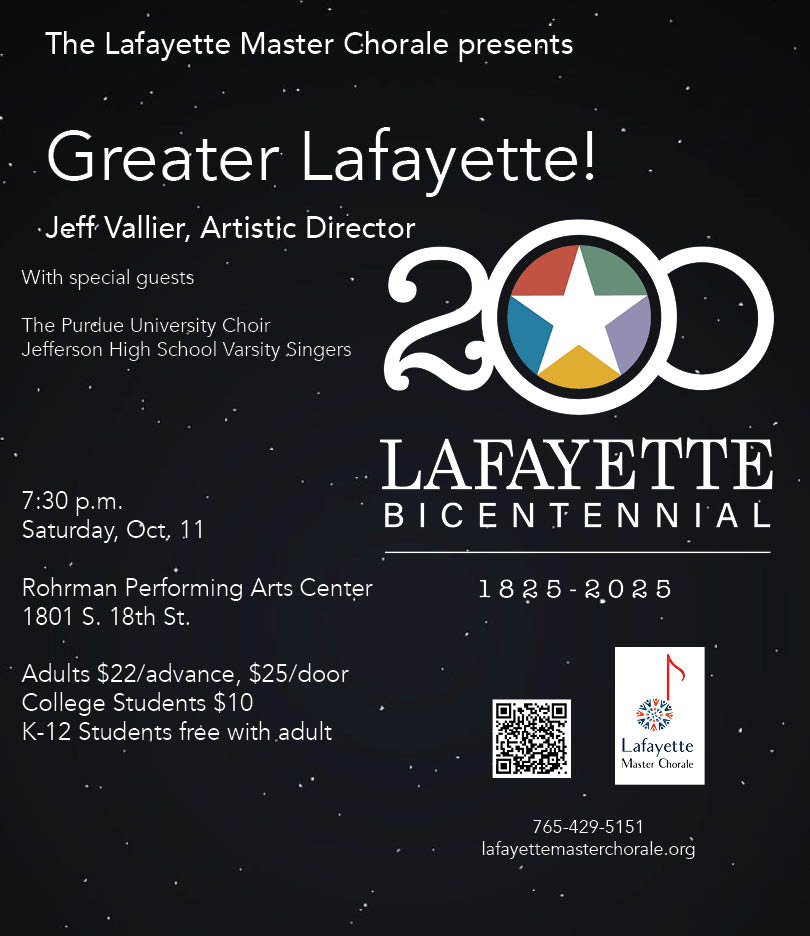

Support for this edition comes from Lafayette Master Chorale, presenting Greater Lafayette! at 7:30 p.m. Saturday, Oct. 11, at the Richard Jaeger Theater, Jefferson High School, 1801 S. 18th St., Lafayette. Season 61 will begin with a rousing tribute to this great city we call home, as the City of Lafayette celebrates its Bicentennial. The Lafayette Master Chorale will be joined onstage by the Jefferson High School Varsity Singers and the Purdue University Choir as they join voices to sing praises to this city on the Wabash. Tickets – adults $22/advance, $25/door; college students, $10; K-12 students, free – at lafayettemasterchorale.org

Q&A: AUTHOR RYAN COLE ON THE STORY OF LAFAYETTE’S ‘LAST ADIEU’

In this, the city’s 200th year, the story is being retold about how founder William Digby latched onto the name Lafayette for the tracts of land he platted along the Wabash River in 1825.

Author Ryan Cole puts context to the phenomenon and national frenzy that likely spawned Digby’s inspiration in a new book that details the return of the Marquis de Lafayette, four decades after the French general played a key role in the American Revolutionary War.

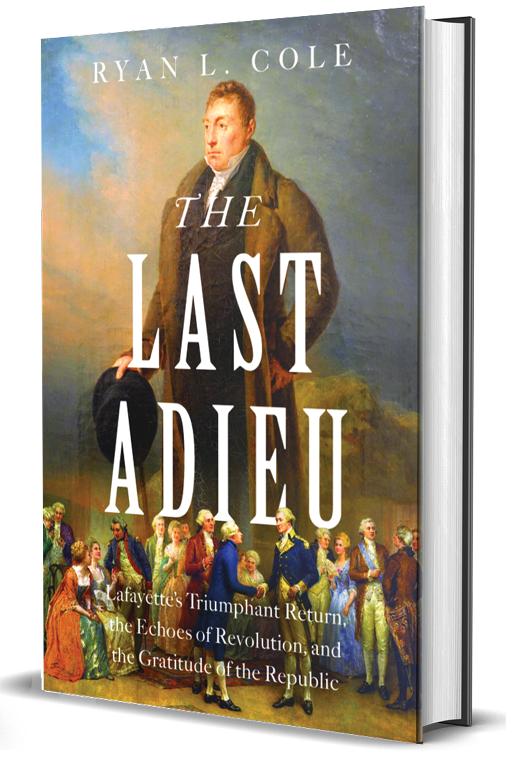

In his new book, “The Last Adieu: Lafayette’s Triumphant Return, the Echoes of Revolution, and the Gratitude of the Republic” (Harper Horizon), Cole details how the war hero’s tour of the U.S. in 1824 and 1825 turned into a sensation in cities large and small in a nation on the verge of its half-century mark.

Cole – a Bloomington resident who has worked at various times for U.S. Sen. Todd Young and former Gov. Mitch Daniels, and is author previously of “Light-Horse Harry Lee: Rise and Fall of a Revolutionary Hero” – spoke to BiL about his new history of the stir Lafayette made across 13 months in a tour that took him to all 24 states at the time.

Question: How’s the rollout been going since the book release in September?

Ryan Cole: It’s pretty good. I got to go to Mount Vernon and give a talk. And then I was in Nashville to speak at the Hermitage, Andrew Jackson’s home. It’s just fun going to these places. When you write a book like this, this is kind of ideally where you like to go share the story. So, I felt really good about, in particular, the one in Nashville. I got to wander around the estate and the grounds for a little bit, which was very beautiful. I don’t know if you’ve been, but there’s a weight to the place, because Jackson’s such a complicated figure. All in all, I had a good experience there.

Question: With a book like this, does it become kind of a historical site book release tour?

Ryan Cole: Those are the venues I like going to. This book is unique in that there’s so many historical sites associated with the story that still exist. In a marketing sense, it kind of puts a whole plan together for you. I’ve got some stuff lined up at historical societies and libraries and things of that nature, as well. But I really love going to the historical sites. You get to go walk around the grounds and then you get to tailor your discussion around that place and the person that lived there. In Nashville, it was very Jackson-centered, because Lafayette spent an afternoon there with Jackson. When Lafayette came to Nashville, everything was Jackson. Jackson was everywhere, because it was a point in our history where he’s become the central figure of our politics. There are so many sub-characters in Lafayette’s story, and Jackson and the dawn of his era is one of them.

Question: Is there a dream spot connected to the book that would be cool to go to in that same sense?

Ryan Cole: It probably would be Mount Vernon, and we got to do that right out of the gate. But since you asked, Monticello. Just because it’s such a fascinating, beautiful place, it would be awesome to go to Monticello. Lafayette visited there twice during his trip to America.

Question: How did this project get started for you? Why Lafayette and why his return to the United States?

Ryan Cole: The first part of my answer is a little disappointing in the sense that I know there are people out there that love Lafayette. There’s the American Friends of Lafayette with, I think, a couple thousand members, at least. There are a lot of young people because of “Hamilton,” the musical. Funny, I talk to friends who have teenage kids. They may not know a lot about Lafayette, but their kids sure do, and it’s almost always because of “Hamilton.” So, I admire him, I think that his story is fascinating. He’s a noble, idealistic character, and his life is amazing. But I didn’t want to write a biography of Lafayette, partly because there was one that came out a couple years ago that Mike Duncan wrote (“Hero of Two Worlds: The Marquis de Lafayette in the Age of Revolution”), and then maybe a decade before, Laura Auicchio wrote one (“The Marquis: Lafayette Reconsidered.”). Both really good biographies, and I didn’t have a lot to add.

But this story where he’s the star – not a biography, but he’s the star – I had read about in those biographies and in histories of the of that time period. I always found it incredibly fascinating and compelling. But I was curious about more. I wanted to know about the mechanics. How did it get organized? How did he decide to come here? How are things planned? And then most of all I wanted to know about, how was the everyday American viewing his return? What were they experiencing and feeling along the way? I didn’t think any of the books that existed dug too deeply into it, maybe a chapter in a book about Lafayette. So I was curious about, could there be an actual book about the tour, and could I get into and answer my own questions about those aspects of the tour? That was the genesis of it

.

Question: You have him decades after the American Revolution, in 1824, where his life had been a real roller coaster back home, right? When he gets the invitation to return to America, it takes him time to clear his debts and figure out if he can even go and if he’s well enough to go, as he’d always hoped.

Ryan Cole: Yeah, I think that his legacy, then and now, obviously, is his participation in our Revolution, not the French Revolution. And you just pointed to another one of the reasons why I thought this was such a good story, was that it’s a great drama. Because you have this old hero who’s weathered, like you said, a roller coaster life. He had that roller coaster beginning in 1818, when he returns to politics. It started to inch upwards, but it’s going back down by the time he gets the invitation to come to America. I like to say he needed to come to America. And because of all the things happening in America at the time, we both needed each other the most when it happened. But this ability for him, at this low point, to come to America, part of it’s political to be able to come here and say representative government is working, and take that message back to Europe. But it’s much more than that. It’s that he needed to have these reunions with old veterans of the Revolution. He needed all this adulation. And I think he needed the affirmation to see that this experiment that he participated in was working and freedom was spreading – imperfectly, obviously. He notes that in his correspondence. But the American Revolution had succeeded. And I think that was a great affirming thing for him at that point in his life.

Question: You talk about both sides needing this trip. But you paint a picture of a guy who really enjoyed his own reputation. You write about how others spoke about Lafayette looking for a pedestal. Is that a fair way to tell it? And that he found it here in the States?

Ryan Cole: Like no one else has ever found it here, probably. The journalist Hezekiah Niles, whose Niles Register was one of the first, if not the first, magazines published in the United States, his chronicling of the trip was wonderful. His famous quote is that there’s no parallel, that “no one like Lafayette has ever reappeared in any country.” And I think that’s true. The adulation he got, I don’t think anyone’s ever experienced that. But there was another famous quote, from Thomas Jefferson, who said Lafayette had a “canine appetite for popularity and fame.” And, boy, was it satiated.

An interesting thing in my research is that he hired a secretary, Auguste Levasseur, to come along and chronicle the trip and help write speeches and correspondence. (Levasseur’s) published journals of the trip are the primary document when you’re trying to learn about the whole voyage. I was able to look at some of the letters Levasseur wrote back to France during the trip. Early on in the trip, when they’re coming back from Boston – they get to New York in August, then they go up to Boston almost immediately, and then come back down to New York – and Levasseur was writing that everyone else in their party is sick and tired because of the exhaustion of the travel, of the shaking hands and the events, the dinners, the speeches. He says, not Lafayette. It’s like he’s 20 again, is what Levasseur says. He was so rejuvenated at a low point in his life, both personally, politically, even his health. Then coming here, almost immediately, it’s like a lightning bolt brought him back to life.

THANKS FOR SUPPORTING THE BASED IN LAFAYETTE REPORTING PROJECT.

Question: This far removed from the Revolution, there’s no “Hamilton” then for kids to latch on to. What was the enduring memory of him by that point? A lot of his contemporaries, including his friend George Washington, were not necessarily there. What was the fascination at that point?

Ryan Cole: First of all, I think Lafayette was different. Even in 1824, he was different. There were scores of Europeans who fought in our Revolution. We have counties here in our state named after them. But Lafayette was different in the sense that he ingratiated himself to the American army, to the American people, early on. He readily adapted to American customs and to particular political ideals in a way that his fellow European soldiers of our Revolution didn’t. There are great anecdotes about how a lot of the European soldiers hated that they’d fight alongside American soldiers who were actually farmers or tavern keepers. These were professional soldiers with European armies. That didn’t bother Lafayette, who famously, in his memoir, said the first time he viewed the American army, Washington turned to him and said, we must be so embarrassed for you, this French soldier, to see a ragged army. Lafayette says, I’m here to learn, not to teach. I think early on, that and his sacrifices – obviously beginning with him being shot at Brandywine, culminating in the siege of Yorktown, eventually leading to our independence – plus Americans following the tumult of his life during the French Revolution and afterwards, gave him a special place among Americans who would have been reading about him and following him.

One thing I try to distinguish in my book is that I don’t think it was just him. What you’re seeing with American reaction to his return, it was about the Revolution, in general, and the other veterans of the Revolution. There was revolutionary nostalgia in the years leading up to that. I mean, let’s bring it back to Indiana. You’ve got Montgomery County, just south of Lafayette, founded and named just before that. I’m in Monroe County, founded in the 1810s. If you look at the maps, it dawned on me in the process of writing this book, I could hardly drive across the state without going through a county that wasn’t named for a revolutionary hero or veteran. If you’re leaving Indy and going down to Bloomington, you’re going through Marion, you’ll go through Morgan, you go through Monroe. Most of these were founded in the years before Lafayette’s visit. So, there was a nostalgia already. You can see it in prints of the Declaration that were made available. And histories. Niles did a book which was a collection of the speeches from revolutionary figures. This is all happening in the years preceding Lafayette’s visit. There was obviously a nostalgia as we neared the 50th anniversary of the Declaration, so I think the ground was already fertile for this incredible explosion of joy and this feeling about the past.

You can also think of it this way: You and I probably would have been living near a veteran of the Revolution, or we would know someone who was a veteran of the Revolution, or maybe your father or your grandfather. There was still such a close, real connection to the era at that point. You have to put this all in this stew of emotions that resulted in this huge phenomenon around Lafayette’s return.

Question: Have you found a comp to someone or a situation in recent history to what the reaction was to Lafayette’s visit?

Ryan Cole: No, I haven’t. Part of it, to get to Niles point about no one ever reappearing like Lafayette, is that, especially today, Lafayette was not identified with any state or any region, no political party. He’s a very unique figure that we don’t have. It’s very hard to see anyone like that emerging, having that kind of effect. The only comparison I could make is that there’s been a couple times, I think, in our lives where the country has something happen that has pushed the country in a place where we were, for the moment, prioritizing our common citizenship and values over our partisan divisions. I guess 9/11, for a period, was like that. I would guess that Pearl Harbor had a feeling like that. Where something happens in the country, where we’re reminded of the things that we have in common, and for a period, are able to prioritize that. Obviously, politics are important and disagreements important. But there are moments where it’s useful to be reminded of our common history and values. 9/11 is not the greatest comparison, because it’s a terrible, tragic thing, and Lafayette’s return is a happy thing. What I’m trying to get at is that there are moments where the country stops what it’s doing and for at least a period rallies together around something.

Question: You did have the nation’s Bicentennial in 1976, where history was everywhere, everything was red, white and blue, towns were painting fire hydrants to look like Revolutionary soldiers, Bicentennial moments were on TV night, all of that.

Ryan Cole: All I remember is when I was a kid seeing the Bicentennial quarters. That was legacy to me. I was so fascinated by the quarters. I would really love to know about the planning for the Bicentennial, but I think a lot of it was federal – like the federal government and the states did a lot of planning. The Lafayette return is interesting, because when he got here, the original itinerary was to go to New York, to Boston, back to New York, and then start moving west, toward the capital. A lot of that was intentional, because he didn’t want to go immediately to D.C. to give the impression that it was organized by the government – even though he’d been invited by Congress – but that it was the trip of a private citizen. That allowed the space where there was a lot of local planning. I’m amazed by the fact that there’s incredible celebrations in more populous cities, like New York, Boston, Philadelphia, but even when he was on the frontier, where there were fewer resources and fewer people, they still did everything possible to celebrate him.

One of my favorite examples is that when he crosses from Georgia into Alabama, he’s carried across the Chattahoochee River by a band of Creek warriors. And one of the members of the Alabama militia there watching it said it was the greatest crossing of a river he’d ever seen in his life. Even if you’re far away from centers of population and barely settled parts of the country, they still were having these incredible celebrations to greet him and bring him to their part of the country.

In fact, there’s a letter to John Jay from Timothy Pickering, who was adjutant general of the Revolutionary Army, who is kind of cynical about this, saying that Lafayette was a great soldier, but he was no Nathanael Greene, and this is not really befitting the character of our republic. That it’s nothing more than just a competition between towns and cities. I think, though, because of that, it’s more to the nature of why it’s such a huge event.

Question: Would he have known about all the cities being named for him in real time? William Digby named this Lafayette in spring of 1825, in the middle of Lafayette’s trip.

Ryan Cole: Some of them, not all. I didn’t see anything in correspondence where Lafayette was getting word, for example, of Lafayette, Indiana. I got asked this question when I was talking at Mount Vernon. It’s very hard to pin down how many places were and are named for him. Some historians have said 600. But it gets murky, because there are places that are named Lafayette or Fayette that aren’t named for him, or that were named for another place that was named for him. I just usually say hundreds. He would have been aware of some of them. But beyond the naming of places, you had lakes, mountains. In Nashville, there was a professorship named for him. You had babies named for him. You had charities named for him. Some of those he would have been present for, so he obviously was aware of the larger trend to name things in tribute to him. …

Thinking about William Digby, you could make the case that this is a popular cultural phenomenon, this tour and the reaction. The comparison that people always really enjoy is Taylor Swift and the Eras tour, because there’s all this merchandise and you had to pay to sit in a tree in Boston to watch him go by in a carriage, and people just wanted to touch him. It’s a fun comparison, but when you think about Lafayette and William Digby, my sense is that it was that people were naming places because it was a popular thing. But I also sense they felt they were doing something patriotic by naming it after Lafayette.

I feel that way because one of the things about this book that I tried to do as much as possible was to bring in the perspectives of the people who were there – whose names we don’t know, who are lost to history, who were in the crowds. I was able to find a lot of letters that they wrote to friends or relatives about what they were seeing and what they were feeling. And I was kind of surprised in the sense that a lot of them were wrestling with what was happening. They were probably more connected to our founding values than we are, obviously, because it was only a generation away. But they were wrestling with the idea of, is it compatible with our republican nature – small-R republican – to be worshiping a man like this. Is this not idolatry? And then they would come around in these letters and say, Well, if there was ever an occasion to do it, it’s now, because of this veteran of the Revolution and all the other veterans of the Revolution who are turning out to see him – even the widows of the veterans – and we owe them gratitude. And now is the moment to offer it. In this case, it’s all right. I feel like that’s connected to the naming of places – that maybe William Digby was thinking, not just that this is something that’s popular, but also by naming this community Lafayette, I’m offering my own form of gratitude to the veterans of the Revolution. At least I like to think of it that way.

Question: You give land speculators a lot of credit.

Ryan Cole: Digby was a real rover, right?

Question: He bought land betting on where it was along the river. It’s a pretty complicated history. But he was a character, for sure.

Ryan Cole: I kind of warned myself, the more and more I got away from Lafayette in trying to tell the story, the more readers probably would be checking out. So I had to be mindful of not getting too far away from him. But there’s so many interesting characters, particularly when he comes to the west, that match that description, who are the founders of places he’s going to. It’s this second generation of Americans who are spilling west. There are a couple of stories in the book of people who came west to actually try and reconcile the imperfections of America, as it was in 1824, with the Founders’ grand idealism. But there were also a lot of scoundrels, right? A lot of rounders, a lot of squatters. The whole picture of the West that Lafayette’s traveling through was fascinating to me.

FOR MORE: “The Last Adieu: Lafayette’s Triumphant Return, the Echoes of Revolution, and the Gratitude of the Republic” was released by Harper Horizon in September. Author Ryan Cole will be speak at a book release event at 6 p.m. Oct. 14 at the Indiana History Center, 450 W. Ohio St. in Indianapolis. For more details and tickets, here’s a link.

Thanks, again, for support for this edition from Lafayette Master Chorale, presenting Greater Lafayette! at 7:30 p.m. Saturday, Oct. 11, at the Richard Jaeger Theater, Jefferson High School, 1801 S. 18th St., Lafayette. For tickets: lafayettemasterchorale.org

Thank you for supporting Based in Lafayette, an independent, local reporting project. Free and full-ride subscription options are ready for you here.

Tips, story ideas? I’m at davebangert1@gmail.com.

Mike Duncan's "Hero of Two Worlds" is one of my favorite books. Love seeing a shout-out to it.

My favorite account is the book, "Lafayette in the Somewhat United States" by Sarah Vowell.