Richard Allen’s appeal focuses on what wasn’t said in Delphi murders trial

Questions about why third-party theories about ritualistic murder, doubts about prosecution’s timeline, suspect sketches weren’t allowed in 2024 trial at the center of filing at Court of Appeals.

Support for this edition comes from Our Saviour Lutheran Church. We warmly invite you to attend our Christmas Eve Service, on Wednesday evening, Dec. 24, with Christmas themed music beginning at 6:30 p.m. and worship at 7 p.m. This service is available both in-person and online, so you can participate from wherever you are. Join us in person at 300 W. Fowler Ave. in West Lafayette, or connect with us virtually through our Facebook (facebook.com/osluth) or YouTube (youtube.com/@osluth). Our phone number is 743-2931. Service highlights: reflecting on God’s love; celebrating the birth of Christ through meaningful scripture readings; candle lighting ceremony; singing of traditional hymns; and participating in communion together. We look forward to gathering as a community to honor the spirit of Christmas and rejoice in the birth of Christ. All are welcome on this special evening of worship and celebration.

RICHARD ALLEN’S APPEAL FOCUSES ON WHAT WASN’T SAID IN DELPHI MURDERS TRIAL

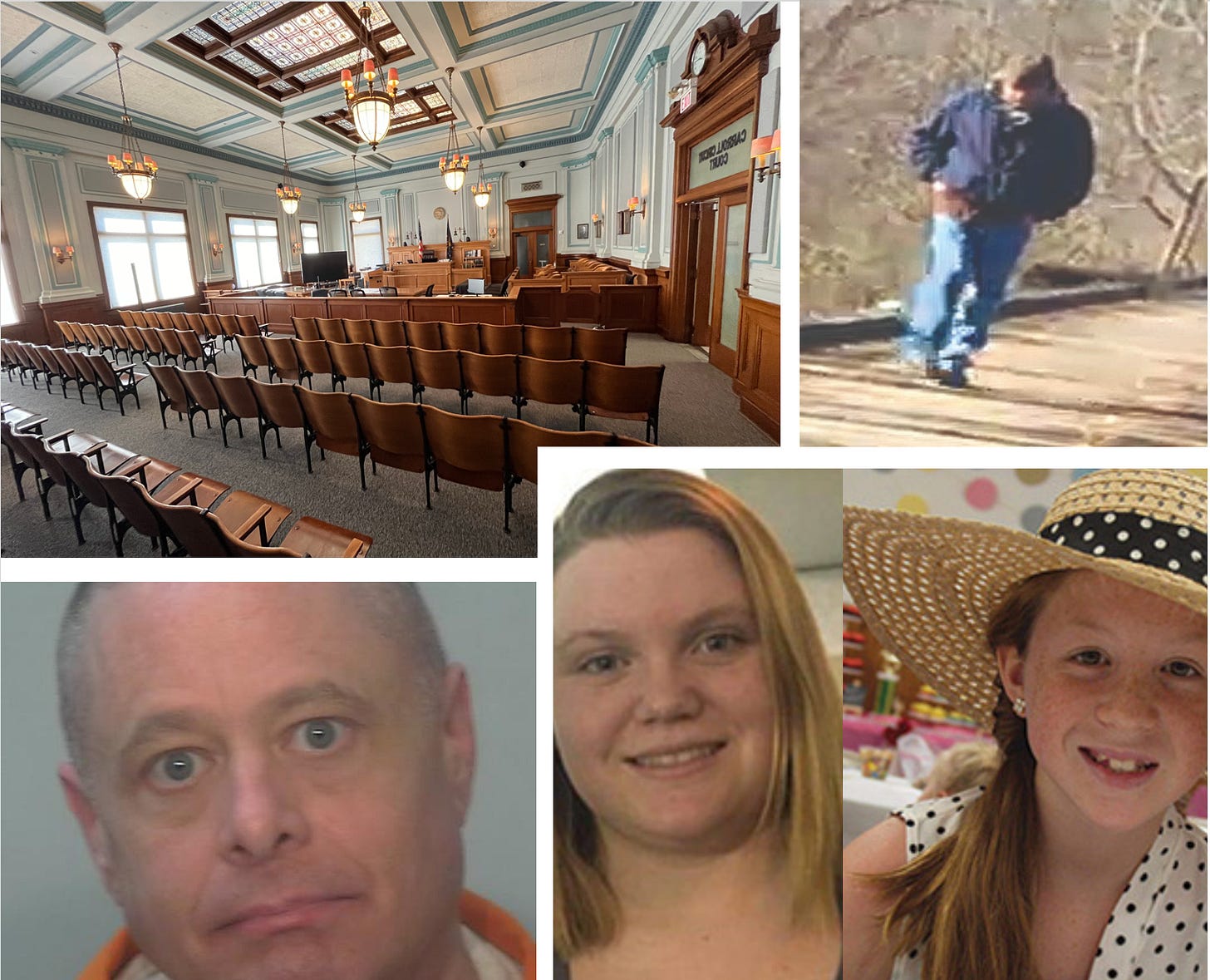

Attorneys leading an appeal for Richard Allen, the Delphi man convicted in the 2017 murders of Abby Williams and Libby German, filed a 113-page brief Wednesday, arguing that the court made a series of errors during and leading up his 2024 trial that tamped down evidence Allen’s defense team wanted to offer.

In arguments signaled in recent months, court-appointed attorneys Stacy Uliana and Mark Leeman contend that the court refused to consider what the defense called “false statements and reckless omissions” by investigators when they asked a county judge for a warrant to search Allen’s Delphi home in the weeks leading up to his October 2022 arrest

.

The brief filed with the Indiana Court of Appeals also argues that Judge Fran Gull erred by allowing the jury to hear a series of statements Allen made that he was the killer, ignoring that the admissions were made “while gravely ill” and broken by months of “unprecedented pretrial solitary confinement” in an Indiana prison.

The brief – coming in with a court-approved extra 10,000-word limit due to the complexity of the case – also argues that Allen’s defense team was blocked from offering evidence tied to a theory that the girls were murdered by others as part of a ritualistic killing tied to a pagan Norse religion.

“Because the trial court prohibited the jury from hearing Allen’s side of the story showing how law enforcement went down the wrong path, justice could not be done,” Allen’s attorneys wrote.

The next step: The state has 30 days to respond.

Allen was convicted in November 2024 after a trial that lasted nearly five weeks, including selection of a jury from Allen County due to the high-profile coverage of a case to took 5½ years to produce an arrest.

Gull, an Allen County Superior Court judge appointed to the case shortly after Allen’s arrest, sentenced him to 130 years in prison.

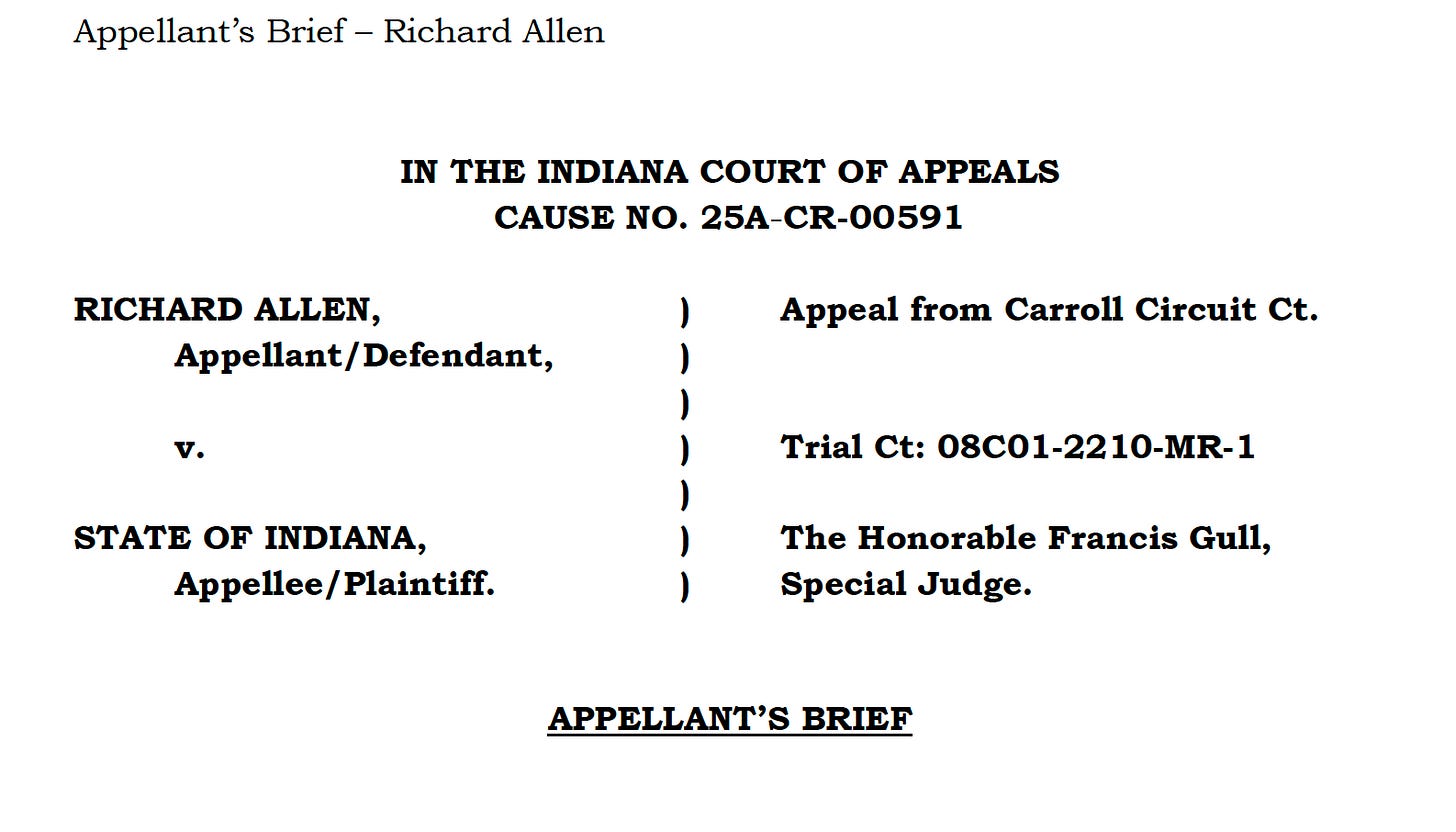

Abby, 13, and Libby, 14, each eighth-graders at Delphi Community Middle School, were killed Feb. 13, 2017, after being dropped off to spend time during a day off from school on the Monon High Bridge Trail, part of Delphi’s trail system. They were found dead in the woods the following day, their necks slashed. Despite video found on Abby’s phone of a man following them on the Monon High Bridge, the case went without an arrest until investigators zeroed in Allen, who admitted to being on the trail that day but denied that he was the “Bridge Guy” in the video or the one who killed the girls.

The trial was built around a prosecution case that said Allen was, in fact, Bridge Guy, linking him through dozens of admissions months after his arrest and – despite no DNA evidence at the scene or in a search of his house five years later – to an unspent bullet found at the crime scene that investigators say had been in a gun later found in a search of Allen’s home.

Allen’s defense team was frustrated during the trial and by a series of pre-trial rulings by Gull that they said hamstrung the case.

The filing asking to reverse Allen’s conviction leans into several of those moments.

The warrant to search Allen’s home

The brief details that Allen went to police in the days after Abby and Libby were killed, telling an officer that he’d been on the Monon High Bridge trail that day.

“After the interview, the lead was marked ‘cleared,’ and the report was misfiled,” his attorneys wrote in the brief. “Allen then returned to his job, family and home in the small Delphi community. For the next five years, he did not sell his car, destroy his clothes, dispose of his gun, or relocate, but continued his normal routine. No witness identified Allen as Bridge Guy. When the report was rediscovered in September 2022, law enforcement insisted Allen was Bridge Guy without a single eyewitness. Over the next several years, the State built its case against Allen.”

Allen’s attorneys contend that Gull should have granted a Franks hearing ahead of the trial to deal with an attempt to prove investigators lied or hid crucial evidence from a judge when they received a search warrant for Allen’s Delphi home in October 2022. In those motions, Allen’s trial attorneys Brad Rozzi and Andrew Baldwin had leaned into a theory that suggests the girls were ritually sacrificed by worshippers of Odin, not by Allen. Allen’s attorneys wanted to suppress evidence from the search of his Delphi home, including a gun that investigators contend matches the ballistics of an unspent bullet found near the girls’ bodies in the woods along Deer Creek. The prosecutor had pushed back on those accusations.

The brief filed this week argues that then-detective Tony Liggett – now the Carroll County sheriff – got the warrant after misleading a county judge by “omitting and altering witness descriptions to connect Allen to ‘Bridge Guy,’ and by misrepresenting that Allen admitted he wore a blue Carhartt, like Bridge Guy.”

The brief contends that Liggett “misled the court in four ways,” including that descriptions offered by witnesses on the trail in 2017 – ones that led to sketches distributed to the public during the investigation – indicated Bridge Guy had “brown ‘poofy’ hair … was in his 20s or early 30s, youthful and medium build.”

“At the time of the murders, Allen was 44 years old, 5-foot-6 and had very short hair,” his attorneys argued.

The brief contends that Liggett left out a witness’ description of a man walking on a county road near the trail that day wearing a tan coat. It also argues that Liggett told the judge that Allen had admitted to owning a blue Carhartt but left out that jacket Allen had was one his wife said in 2022 that he had bought “a couple of years ago.”

“Had the court known Allen simply admitted owning a blue or black coat – as does probably every 50-year-old man – it would have known there is no connection between him and Bridge Guy,” Allen’s attorneys argued.

“These misrepresentations and omissions misled the judge into believing multiple witnesses saw Allen and his car, when in fact they described someone else and a different car,” Allen’s attorneys argued in the brief. “Once the affidavit is corrected, there is no probable cause. … Without the fruits of the search – the gun, a casing in a hope box, the Carhartt, knives and computer – the State cannot prove the jury would have convicted.”

The brief takes issue with Gull refusing to hold a Franks hearing to consider whether the warrant was properly obtained.

“Tellingly, the trial court was willing to schedule a Franks hearing when Allen was represented by Fort Wayne attorneys but refused when the original attorneys were reinstated,” the brief contended, referencing a move Gull made to remove Baldwin and Rozzi from the case before the Indiana Supreme Court reinstated the defense team. “Allen’s constitutional protections are not contingent on who his attorneys are.”

Allowing jurors to hear confessions made by Allen

The brief argues that Allen wasn’t well physically or mentally when he told his wife, mother and inmates and guards assigned to watch over his cell at Westville Correctional Facility that he killed Abby and Libby.

Moved from Carroll County Jail days after his arrest as part of a safekeeping order, Allen spent 13 months in a state prison, largely in solitary cell in a segregated portion of the prison, when prison policy suggests a 30-day limit on solitary confinement.

“Early in custody, Allen maintained innocence and believed solitary was meant to ‘tear him down,’” his attorneys wrote. “He told the psychologist, Dr. (Monica) Wala, he felt like a ‘broken man’ after two weeks.”

The brief describes Allen’s behavior “suddenly worsened” in late March and early April 2023, with his weight dropping from 180 pounds to 135. They wrote that “he ripped legal mail, washed his face in the toilet and drank toilet water.” The brief describes him as refusing meals, hitting his head against his cell wall, acting like he was from medieval times, “stuck a spork into his genitalia, and covered himself in feces, spit, and vomit.” A prison psychiatrist, after seeing “him naked, covered in feces, with brown fluid from his mouth from eating it,” found Allen “‘very psychotic,’ hallucinating, and incompetent to consent to treatment … ordered involuntary medication and found him ‘gravely disabled.’”

“When Allen’s attorneys informed the court of his dire condition,” the brief contends, “the court also refused to move him, and the prosecutor delayed and mocked counsels’ concerns while collecting evidence of Allen’s confessions.”

A string of those calls Allen made were played for the jury during the final day of the state’s case.

From the brief:

“Also, the jury did not hear Allen, the morning he started confessing, tell his family in three intertwined calls that he was confused and losing his mind.

“In the first call at 3:12 am on April 3, Allen told his dad he was losing his mind and was uncertain how much longer he was ‘going to be lucid.’ Allen said, ‘You guys know I would never do something like I’ve been accused of.’ Allen felt he had been mentally tortured, like he is in Guantanamo Bay, and that there were drugs in his coffee and Kool-Aid.

“In the call the jury heard, at 5:14 am, Allen told his wife for the first time he thinks he killed A.W. and L.G. and ‘evidentially did it.’ Allen could not remember what he told his dad in the earlier call.

“Then, in a third call at 8:45 a.m., a panicked Allen told his wife he was not sure if his original call to her was a dream. He said he was not drinking the water or the coffee and questioned whether the attorneys who were coming to visit him were his attorneys.”

“The jury only heard the second call with the confession, along with (Indiana State) Trooper (Brian) Harshman’s opinion that Allen showed no ‘indication’ he was under ‘duress or stress’ when he made that admission.”

The brief argues that Allen’s statements weren’t made voluntarily, but were essentially coerced by the effects of prolonged solitary confinement on his mental state. Allen’s attorneys also argue that being sent to a state prison before his trial was unprecedented and unconstitutional.

“Even if this Court finds Allen’s statements were voluntary because he was not interrogated by law enforcement, he was still gravely disabled when he confessed,” the appeal brief argues. “As such, his free will did not purge the taint of his illegal detention. The trial court erred by denying the motion to suppress.”

Denied a right to present a complete defense

Allen’s attorneys point to several areas where pretrial rulings limited the defense.

The sketches: On the first day of jury selection in the trial in October 2024, Prosecutor Nick McLeland filed a motion to block Allen’s defense team from referring to pair of composite police sketches investigators used for years to generate tips after the 2017 murders. Stacey Diener, part of the prosecution team, argued the day before testimony started that prosecutors believed the sketches would be part of the opening statements by the defense. Diener said the prosecution didn’t plan to bring the sketches – one released four months after the murders in 2017, the second in 2019 – into the trial or to call either of the witnesses who helped forensic artists pull together the facial features to testify about them. Diener said investigators also had three other sketches never released to the public, used as a tool for investigators only. Allen’s attorneys argued that the prosecutors understood that sketches didn’t look much like Allen. Gull sided with the prosecution and the sketches weren’t shown to the jury.

“The State concedes that Bridge Guy’s identity was ‘crucial to the case,’” Allen’s attorneys argue in the appeal. “(The) sketch was critical to Allen’s defense of mistaken identity, and the judge’s decision to exclude it was arbitrary and disproportionate to any legitimate government interest.”

An expert witness on the bullet markings: Gull sided with prosecutors ahead of the trial to bar testimony by William Tobin, a forensic metallurgist lined up by the defense to testify about the accuracy and reliability of the state’s examination of a bullet found near the girls’ bodies. Gull agreed with the prosecutor, who had argued that Tobin isn’t qualified as an expert in the field of firearms examination. In her ruling, Gull wrote that Tobin “is not a firearms expert, has not training in firearms identification and has never conducted a firearms examination.” She also wrote that Tobin had not examined the evidence introduced in the trial.

The brief filed this week contends the state expert’s “credibility was central to the case, and the judge arbitrarily excluded Tobin.”

The response to a phone data expert’s testimony: During the trial, Stacy Eldridge, a digital forensics consultant for Richard Allen’s defense team, testified that Libby’s iPhone 6S logged an audio output deep in the phone’s software, suggesting that headphones or a car aux cable was put into the phone’s jack port at 5:44 p.m. Feb. 13, 2017. She testified that data showed that someone removed the headphone jack at 10:33 p.m. that same night. That testimony challenged the prosecution’s timeline of the murder by hours. That day at trial, Sgt. Chris Cecil, an Indiana State Police phone expert, testified that during a break in the trial he’d Googled possible reasons for the headphone jack issue. He testified that he found reasons on Apple troubleshooting sites including moisture and dirt.

The appeals brief argues that Cecil’s testimony should have been blocked as hearsay.

“The judge arbitrarily allowed the State to undermine Eldrige’s testimony with a person’s internet post, and it was impossible for Allen to impeach the person through cross examination,” Allen’s attorneys argued.

Video, without audio, of solitary conditions in prison: The brief argues that video of Allen’s condition, shown to jurors during the defense testimony, lacked a clear connection to his state of mind without audio that “shows a delusional, confused and disorganized mind” and “a vivid picture of solidary confinement’s harsh conditions.”

“The jury never heard Allen’s confused, disjointed ramblings and screams during the months that Dr. Wala said Allen was making logical and organized confessions,” Allen’s attorneys argue. “The trial court permitted Allen to play 15 videos of him in solitary to impeach his confessions but required Allen to mute them.”

The brief contends that the sound offered a clearer view of man who “begged to be put on an airplane and told (guards) not to believe his last confession;” “asked for his ‘mommy’ and ‘daddy,’ rambled about suicide and time travel, and within seven minutes, claimed to be both the stupidest and smartest person ever, and repeated ‘wait for it;’” and “with feces on his face, he asked to be euthanized and whether his wife was present” and “said he was King Michael, claimed he had started WWIII, tried to save his family and Donald Trump, sang hymns, quoted scripture, and asked to be cryogenically frozen.”

Claims of false testimony: During the trial, prosecutors focused testimony of Dr. Monica Wala, a psychologist at Westville, about a confession she said Allen made to her. Wala had testified that Allen described details about forcing the girls off the Monon High Bridge with the intent of raping them, only to get scared when he spotted a passing white van – a piece of the timeline investigators later said was something only the killer would know. Wala testified that Allen told her that after he saw the van go by, he’d crossed to the north side of Deer Creek and killed the girls there.

During the trial, Brad Weber, a Delphi resident who lives just southeast of the south end of the Monon High Bridge, testified that he got off his shift at the Lafayette Subaru plant at 2:02 p.m. Feb. 13, 2017 – the day of the murders – and drove home. He said it took 20 to 25 minutes to get home. That put him home, based on his testimony, “about 2:30.”

Libby German shot a final video – the one capturing the image and voice of a suspect known as Bridge Guy – at the southwest end of the Monon High Bridge at 2:13 p.m. Feb. 13, 2017. Prosecutors marked the final movement of Libby’s phone at 2:32 p.m. that day, based on tracking data logged by the phone’s Apple Health app.

In January, Allen’s attorneys asked the court to correct errors, calling out Weber’s testimony as false. They included security video footage of a white van pulling into Weber’s lane at 2:44 p.m. that day. They also contend that Weber’s cellphone started to ping at the property at 2:50 p.m. that day and continued deep into that night. They said the footage, collected from a neighbor’s security camera by state investigators, suggest that prosecutors knew Weber’s testimony didn’t fit the timeline and didn’t correct it.

“The false evidence, if corrected, would have shown that Weber’s arrival home was inconsistent with that State’s murder timeline,” Allen’s attorneys argued in this week’s brief. “Thus, Allen’s statements to Wala are inconsistent with the truth and suggest he was delirious. The error requires reversal.”

The ritualistic killing theory: The court spent nearly a full day in August 2024, months before the trial, going over Prosecutor Nick McLeland’s effort to limit words, phrases and implied references during the trial. That included requests to block trial references to Odinism, cult or ritualistic killing, along with the names of six men tied to a third-party defense attorneys Rozzi and Baldwin had been floating. Baldwin and Rozzi filed extensive court documents that attempted to say it would have been impossible for Allen to work alone to abduct Abby and Libby from the Monon High Bridge Trail, get them to go into the woods along Deer Creek and kill them in the timeframe investigators have laid out. Instead, the defense team say Abby and Libby could have been victims of Odinists, headed by a Logansport man whose son knew the girls. They argued several ways this week that the Logansport man – one prosecutors contend had an alibi that allowed investigators to clear him – had posted drawings and pictures on Facebook that were eerily similar to the crime scene. At several turns, Gull blocked those theories – including parts of the investigation that chased those leads, including some raised in an expansive filing by the defense team – and testimony by expert witnesses ahead of the trial.

The brief also noted that interviews with leaders of the Odinist group done in the early stages of the investigation were taped over – something investigators testified was done in error.

“The trial court prohibited Allen from presenting any evidence regarding the manner, quality, and thoroughness of the investigation into this murder as a ritual killing,” Allen’s attorneys argued in this week’s brief. “The omitted evidence created reasonable doubt and raised questions of the utmost importance about the manner, quality, and thoroughness of the investigation that led to Allen’s arrest 5.5 years after the murders. Had the jury heard it, a different result was likely.”

Read the full brief here

Thanks, again, for support from Our Saviour Lutheran Church, 300 W. Fowler Ave. in West Lafayette, inviting you to attend Christmas Eve Service, Wednesday evening, Dec. 24, with Christmas themed music beginning at 6:30 p.m. and worship at 7 p.m. Learn more at facebook.com/osluth.

Thank you for supporting Based in Lafayette, an independent, local reporting project. Free and full-ride subscription options are ready for you here.

Tips, story ideas? I’m at davebangert1@gmail.com.

Thanks for informing us about this appeal.