The day Walt Disney came to Purdue

Here’s the story about how the university wound up, in 1949, hosting the world premiere of Disney’s ‘So Dear to My Heart.’

Here’s something a little different today. Lafayette author Angie Klink offers this bit of Purdue history from 1949, when the Hall of Music hosted the world premiere of Disney’s “So Dear to My Heart.”

THE DAY WALT DISNEY CAME TO PURDUE

By Angie Klink

Walt Disney and his wife, Lillian, boarded a train in Chicago and rumbled south past dormant cornfields and winter-sleepy railroad towns to arrive in Lafayette, Indiana, for Purdue University’s “Walt Disney Day.”

It was Jan. 15, 1949, and Disney with a troupe of actors gathered at Purdue for the world premiere of his new film. “So Dear to My Heart.” The movie takes place in the fictional Fulton Corners, Indiana. While Brown County, Indiana, was scoped out as a set location, the movie was ultimately filmed in Sequoia National Park and San Joaquin Valley in California because the landscapes resembled southern Indiana.

Plans for the star-studded “Walt Disney Day” held in Purdue’s Hall of Music – later named Elliott Hall of Music – had begun the previous fall. Thomas “Tommy” R. Johnston, university publicist, wrote a letter to Purdue President Frederick Hovde on Oct. 19, 1948, that is now preserved in Hovde’s papers in a folder marked “Disney, Walt” in Purdue Archives.

Johnston wrote:

“… Walt Disney of movie fame, from Hollywood, California, will be in the state January 12-19 preceding the premier of a motion picture, ‘So Dear Our Hearts’ (sic) which will be released in 60 Indiana theaters January 19, 20 and 21.

“(It) is being released first in this state at the request of Gene Pulliam, publisher of the Indianapolis Star, who is a personal friend of Disney.”

Many more letters, newspaper clippings, press releases, telegrams and more are preserved in Hovde’s papers and helped to round out this little-known story of Disney’s visit to Purdue.

A representative from RKO Radio Pictures, Inc., the distributor of the film, had visited Johnston and university Vice President Frank Hockema at Purdue and inquired if something could be done for Disney when he was on campus. RKO was one of the “Big Five” film studios of Hollywood’s Golden Age, before ceasing operation in 1959.

It appears that RKO’s publicists considered Purdue an advantageous place to premiere the film, perhaps because of the university’s clean-cut reputation. Or because Purdue, as Indiana’s land-grant university, offered agricultural majors, the cooperative extension service and 4-H and Indiana State Fair connections that aligned with the movie’s plot. Such a celebrity event was also a grand way to kick off Purdue’s 75th anniversary of the year classes first opened at Purdue.

A Purdue News Service press release sent to the Purdue Exponent, Journal & Courier and Lafayette Leader on Dec. 16, 1948, stated, “The film, which is in technicolor, is based on 4-H Club work and reveals an intensely interesting story typical of 4-H Club work in the state. It is full of the interesting events which farm boys or girls only can experience in raising and showing of livestock.”

“So Dear to My Heart” is based on the children’s book “Midnight and Jeremiah,” by Sterling North. It’s about a little boy named Jeremiah who lives in Pike County, Indiana, in 1903 with his Granny Kincaid, played by Beulah Bondi, who was born in Valparaiso, Indiana. Two years earlier, Bondi had portrayed the mother of George Bailey (Jimmy Stewart) in “It’s a Wonderful Life.”

After one of their sheep gives birth to a black-wooled lamb and rejects it, Jeremiah takes it in, much to Granny Kincaid’s chagrin. There are several differences between the movie and the book. In the book the lamb was named Midnight. In the movie Jeremiah names the lamb Danny because he wants to raise him to be a champion after meeting the world-famous race horse Dan Patch, who was born in Oxford, Indiana. The sheep proves to be a handful, but hard financial times prompt the family to train him so he can enter the county fair and win money. After the film was released, North changed the storyline in his book to match the movie.

Disney loved the story because it reflected the life he and his brother experienced growing up in Missouri. He planned to make it into his first fully live-action film. At this point, all of his prior films had been animated. However, RKO, the distributor for all of his movies, convinced him that when people heard the name “Disney,” they expected animation. So, after the live action was filmed, Disney added animation interludes depicted as Jeremiah’s daydreams with pictures in his scrapbook coming to life to teach him various lessons.

$2 ticket, $2.50 meal

Hovde had been in New York during RKO’s first Purdue visit, so in his Oct. 19, 1948, letter Johnston wrote to relay the news that Walt Disney was coming to campus. He told Hovde that RKO had presented the possibility of the university giving a citation to Disney for his “efforts in producing this and other clean pictures and wholesome entertainment.”

Johnston arranged a private showing of the film to the university staff who were planning “Walt Disney Day” sponsored by the Alumni Scholarship Foundation. Two members of the RKO publicity staff attended. Johnston wrote a letter to the invitees stating that the group would discuss “any plans that we may formulate to use Mr. Disney in a special program during the premiere of this film. … Any sort of appearance would be highly popular with the students.”

FOR MORE BASED IN LAFAYETTE, AN INDEPENDENT LOCAL REPORTING PROJECT, CHECK HERE FOR FREE AND FULL-RIDE SUBSCRIPTIONS.

The group decided that while on campus Disney would be honored with a Distinguished Service Citation along with an honorary membership in the Purdue Alumni Association and the class of 1920. At that point, the only other person to have received an honorary membership in the alumni association had been humorist, actor and author Will Rogers.

Proceeds from the premiere would go toward a newly established Walt Disney Scholarship at Purdue. RKO allowed the university to set the admission price, but the studio mandated that tickets could only be sold to students, staff, faculty and honored guests, such as present and past members of the university’s board of trustees and government officials.

A month before the premiere, Disney sent Hockema a letter commending the university. He wrote:

“ … I want you to know I am very grateful to you, personally, the entire Purdue University faculty, the student body and alumni for the wonderful program you have arranged. … It is with humility that we are looking to the tribute that a great university like Purdue will pay to an industry which can do so much good for the development of the moral and mental fiber of our youth.”

Hovde sent a letter to the university faculty and staff inviting them and their families to attend the premiere at $2 per ticket and a gala dinner in honor of Disney and his cast in the Purdue Memorial Union ballroom at $2.50 per meal. All ticket sales went toward the Disney Scholarship “to assist needy Purdue students.” Disney and the cast donated their time and paid their own expenses.

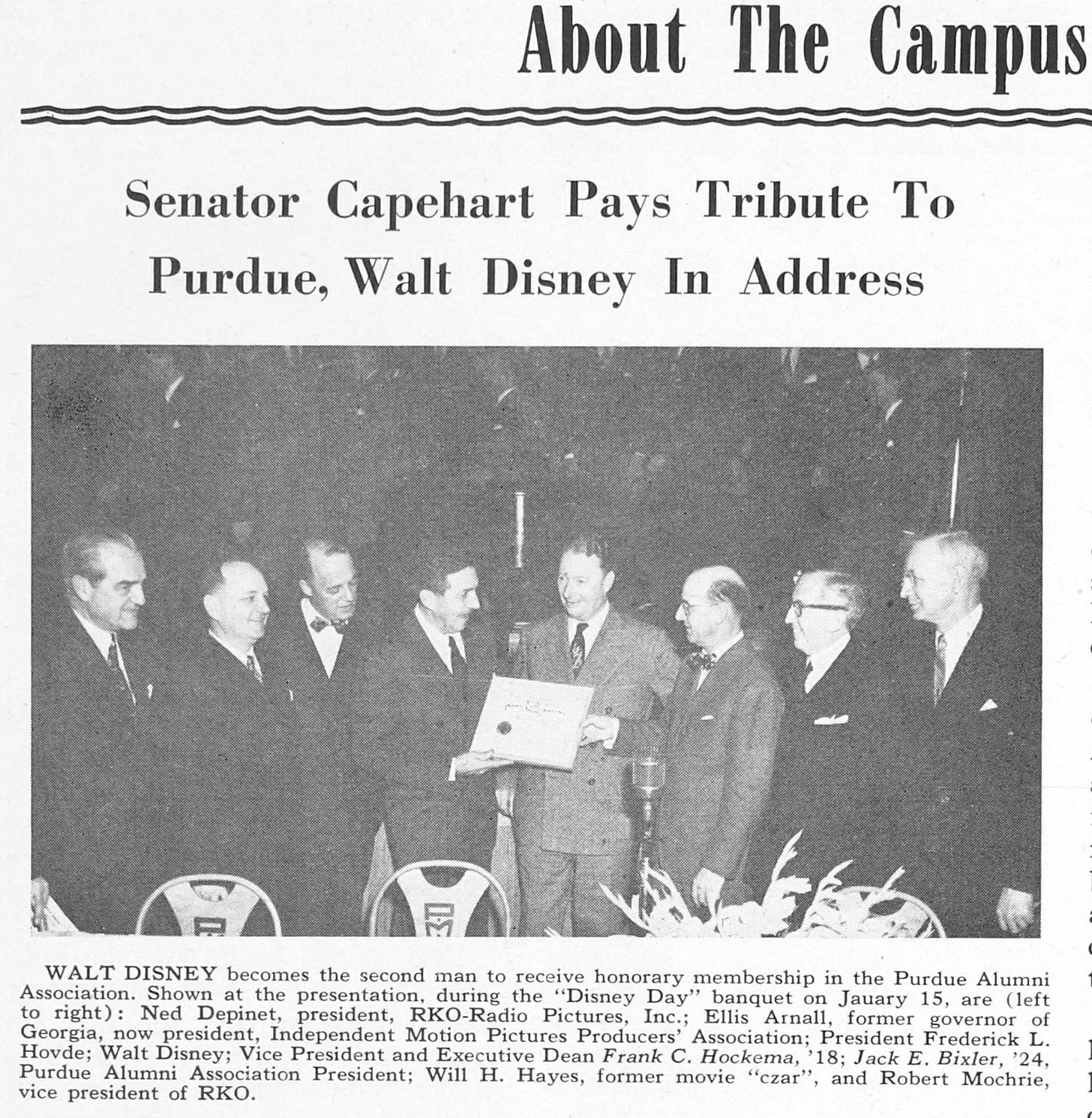

A Journal & Courier story of Jan. 17, 1949, stated that a week before the premiere, Indiana’s Sen. Homer E. Capehart recognized Purdue and the upcoming “Walt Disney Day” in an address on the floor of the U.S. Senate. He said in part:

“ … that great Hoosier institution, Purdue University at Lafayette, Indiana, will celebrate its 75th anniversary. Needless to say, suitable ceremonies have been planned for this memorable occasion. Proper tribute will be paid then to one of the nation’s most outstanding symbols of progress.

“In a few days, the university will pay tribute to another symbol of Americanism. It will present its distinguished service award to Walt Disney and declare him an honorary member of its alumni association.”

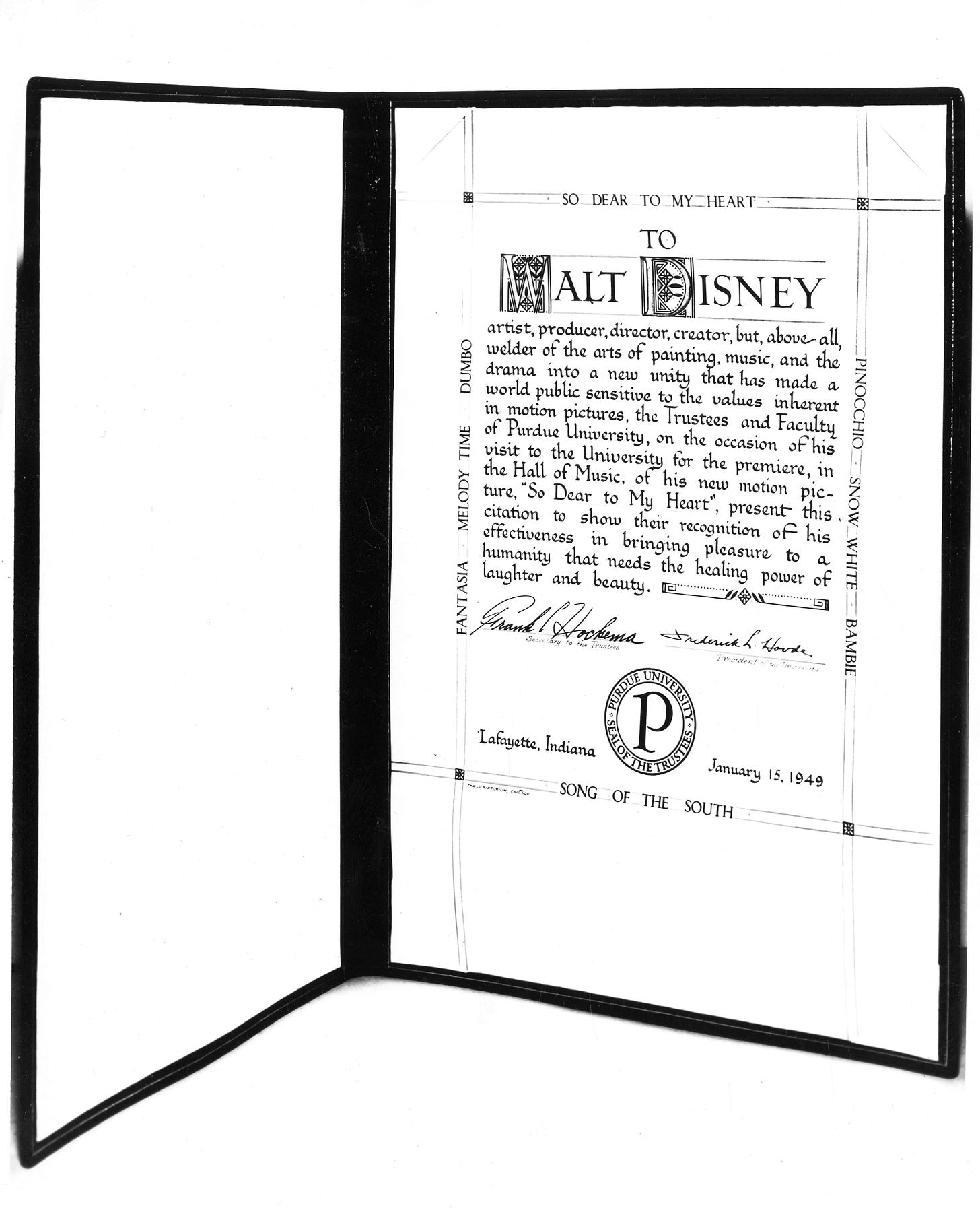

At the end of his address, Capehart read the text on the citation that would be presented to Disney on the Hall of Music stage after the movie screening. These words are now part of the Congressional Record:

“To Walt Disney, artist, producer, director and creator, but above all, welder of the arts of painting, music and the drama into a new unity that has made a world public sensitive to the values inherent in motion pictures. Purdue presents this citation to show its recognition of his effectiveness in bringing pleasure to a humanity that needs a healing power of laughter and beauty.”

As an entourage arrived

The day before the premiere, the Journal & Courier reported that Disney and his troupe arrived at Purdue in the afternoon of Saturday, Jan. 15, 1949, and took a tour of the campus before attending the gala dinner that night. With Disney were the actor portraying Jeremiah, Bobby Driscoll, who would win a Juvenile Oscar for the film; child co-star Luana Patten; Beulah Bondi and her secretary; author Sterling North; and Clarence Nash, the voice of Donald Duck. (A Journal & Courier account said it was announced from the Purdue stage that Nash’s family once lived about 20 miles south, in Colfax, Indiana.) Burl Ives, cast as Jeremiah’s uncle, was unable to attend. Ives may be best known today as the voice of the snowman in the 1964 stop motion animated television special “Rudolph the Red Nosed Reindeer.”

When Disney was presented with his honorary membership in the Purdue Alumni Association at the dinner, he said that if he displayed his membership certificate, he would “have to go back and finish high school.” Disney did not graduate from high school because he left to serve in the aftermath of World War I.

Other distinguished guests were Will H. Hays, former president of what became the Motion Picture Association, Ellis Arnall, former governor of Georgia who was president of the Independent Motion Picture Producers’ Association; and Ned Depinet, president of RKO.

The legendary billionaire, aviator and film director Howard Hughes had purchased RKO the year before and was invited, however his secretary sent a letter of regret to Hockema, stating that Hughes had a previous engagement on the West Coast. Disney’s brother Roy was invited and sent a personal letter: “I regret that I will be unable to attend, but it is not feasible for my brother and I to be away from the studio at the same time.”

Gene Pulliam, publisher of the Indianapolis Star who was a personal friend of Disney and the man responsible for bringing the film tour to Indiana, had a work commitment and sent regrets from himself and his wife. “Walt is a very dear friend of ours, and we are going to feel pretty unhappy about not being able to be with you at your lovely party.”

On the Purdue stage

Al Stewart, director of the Purdue Varsity Glee Club, was master of ceremonies at the premiere and introduced the stars from the Hall of Music stage. The Glee Club sang at both the dinner and the screening, featuring songs from the film. The next day, the Indianapolis Star reported, “Disney and his gang, professional judges of good entertainment, were loud in their praises of the Purdue Glee Club. … They agreed unanimously that it was the best glee club they had ever heard.”

Stewart persuaded the child actors Driscoll and Patten to sing a duet of “Lavender Blue (Dilly Dilly),” as they do with Burl Ives in the film, with the Glee Club singing background. The song would be nominated for an Academy Award that year. According to the Indianapolis Star, a Disney aide said, “I wish we had that recorded.”

A black lamb resembling the one in the film was to have appeared on stage with Driscoll and Patten, but it suffered from stage fright and refused to budge from its backstage crate. Purdue had obtained the lamb from a Chicago packing company.

FOR MORE BASED IN LAFAYETTE, AN INDEPENDENT LOCAL REPORTING PROJECT ...

After the movie and the entertainment, minus the black lamb, President Hovde walked onto the Hall of Music stage and presented Walt Disney with his special citation that had taken Hockema a few months of back-and-forth letters to have created by The Scriptorium, a Chicago company specializing in the hand lettering, designing and illuminating of text. A mockup of the citation is preserved with the Hovde ephemera in Purdue Archives.

Disney’s name appeared in large, decorative type at the top of the citation with his initials in gold. The Purdue seal was centered at the bottom below the signatures of Hovde and Hockema. Much like a diploma, the citation was enclosed in a leather cover.

Early drafts had contained some typographical errors. The main text was framed in a border of Disney movie titles: “So Dear to My Heart” at the top, “Fantasia,” “Melody Time” and “Dumbo” on the left, “Pinocchio,” “Snow White” and “Bambi” on the right, “Song of the South” at the bottom. Even with the a few rounds of proofing and correcting, the final citation contained a misspelled word when it was presented to Disney.

In a letter to Scriptorium written after the premiere, Hockema said, “The Disney citation is beautiful, and it made a great hit with Mr. Disney. … The word ‘Bambi’ was misspelled as ‘Bambie’ on the citation, but I do not believe that Mr. Disney is going to pay any attention to it.”

Scriptorium replied by sending the proof copy of the citation that Hockema had approved with the misspelling along with the message that the company would be glad to make a correction if Mr. Disney wished for it now or later.

The night of the movie premiere Disney and his troupe stayed in the Memorial Union Hotel. The following day the group continued their weeklong tour to promote the film, heading by train to Indianapolis for a theater premiere, then on to Ohio, Kentucky and Tennessee, making headlines in each state. The appearances were also connected to fundraising drives to fight childhood cancer and polio.

A scholarship in Disney’s name

A couple of months later, Disney wrote Hockema a letter of gratitude. “Please accept my thanks and appreciation for the many fine, thoughtful things done by Purdue University for Mrs. Disney, myself and our studio troupe during our recent visit to Lafayette. ... Our reception and the impressions of the day confirmed my respect and admiration for Purdue as one of the great schools of America.”

About 6,000 people attended Purdue’s world premiere of “So Dear to My Heart.” Afterward, Hockema wrote Disney to let him know that Purdue netted $5,500 for the Walt Disney Scholarship fund and the income from the amount would be used each year for student grants. “If in your judgment, these scholarships should be awarded to eligible students who have shown an aptitude for dramatics, cartooning, etc., we would appreciate having your suggestions regarding this matter.” He closed by inviting Disney, his wife and two daughters to return to Purdue for the Notre Dame game that October.

Disney wrote a letter of reply to Hockema on his understated “Walt Disney” letterhead: “I was naturally pleased and interested to know about the financial outcome from the premiere showing of ‘So Dear to My Heart.’ I do not feel there is any reason why these scholarships should be confined exclusively to students showing an aptitude for dramatics, cartooning, etc. I would rather see this fund set up so that any worthwhile student would be eligible to a scholarship.”

According to the Winter 2022/2023 Purdue Alumnus, the first student to receive the Disney scholarship was Charles Woodward, a mechanical engineering major. He wrote Disney a letter of thanks, and Disney responded with a note that said, “It gave me a warm feeling to know that I have done just a little toward launching a young American on the road to a happy and successful life.”

Disney contributed to the scholarship until his death in 1966, and it helped more than 60 students. He closed his March 1949 letter to Hockema saying that he would be pleased to return to Purdue, but that would not be possible as he and his wife were leaving that summer to spend several months in England to film “Treasure Island.” He ended with, “If you are ever out this way, I hope you will give us a call and let us show you something of our fun factory.”

Walt Disney signed his typed letter to Hockema with a fountain pen. At the bottom of the page, his name floats buoyant in thick swirls of black ink, a playful autograph that some say is the most famous signature of all time.

Sources for this story came from the Frederick L. Hovde Papers in Purdue University Archives and Special Collections and various newspaper reports.

Angie Klink is the author of 11 books. She is a historian, biographer, essayist, scriptwriter and copywriter. Learn more at www.angieklink.com

THANK YOU FOR SUPPORTING BASED IN LAFAYETTE, AN INDEPENDENT, LOCAL REPORTING PROJECT. FREE AND FULL-RIDE SUBSCRIPTION OPTIONS ARE READY FOR YOU HERE.

Tips, story ideas? I’m at davebangert1@gmail.com. Like and follow Based in Lafayette on Facebook: Based in Lafayette

I had the great fortune of knowing people whom Walt hired, and one of them, Alice Davis, remained my closest friend until her passing last year (those are her pirate costume designs and her small world costume designs and etc.) Though Walt may have ended his $ contribution to Purdue in 1966, CalArts remains to this day as a major part of his legacy in art and academia (see also Chouinard Art Institute).

Thanks Dave...Thanks Angie. Great story.