Ukrainian family’s escape from war lands in West Lafayette

Mother says after leaving Kyiv: ‘I feel very bad being comfortable here. Family is there. Friends are there. Life is there. Your life is like on mute. I just want home’

Today’s edition of the Based in Lafayette reporting project is sponsored by the Center for C-SPAN Scholarship & Engagement at Purdue. The Center for C-SPAN Conversation with Brian Lamb will feature a conversation with Howard Holzer, Lincoln historian and author, at 6 p.m. April 6 at Purdue. For more, scroll through today’s edition

Safe in West Lafayette, waiting for her son, Glebe, to come home on the bus from his first day at his new school, Olesia Vasylenko is still monitoring the air raid sirens going off near her home in Kyiv.

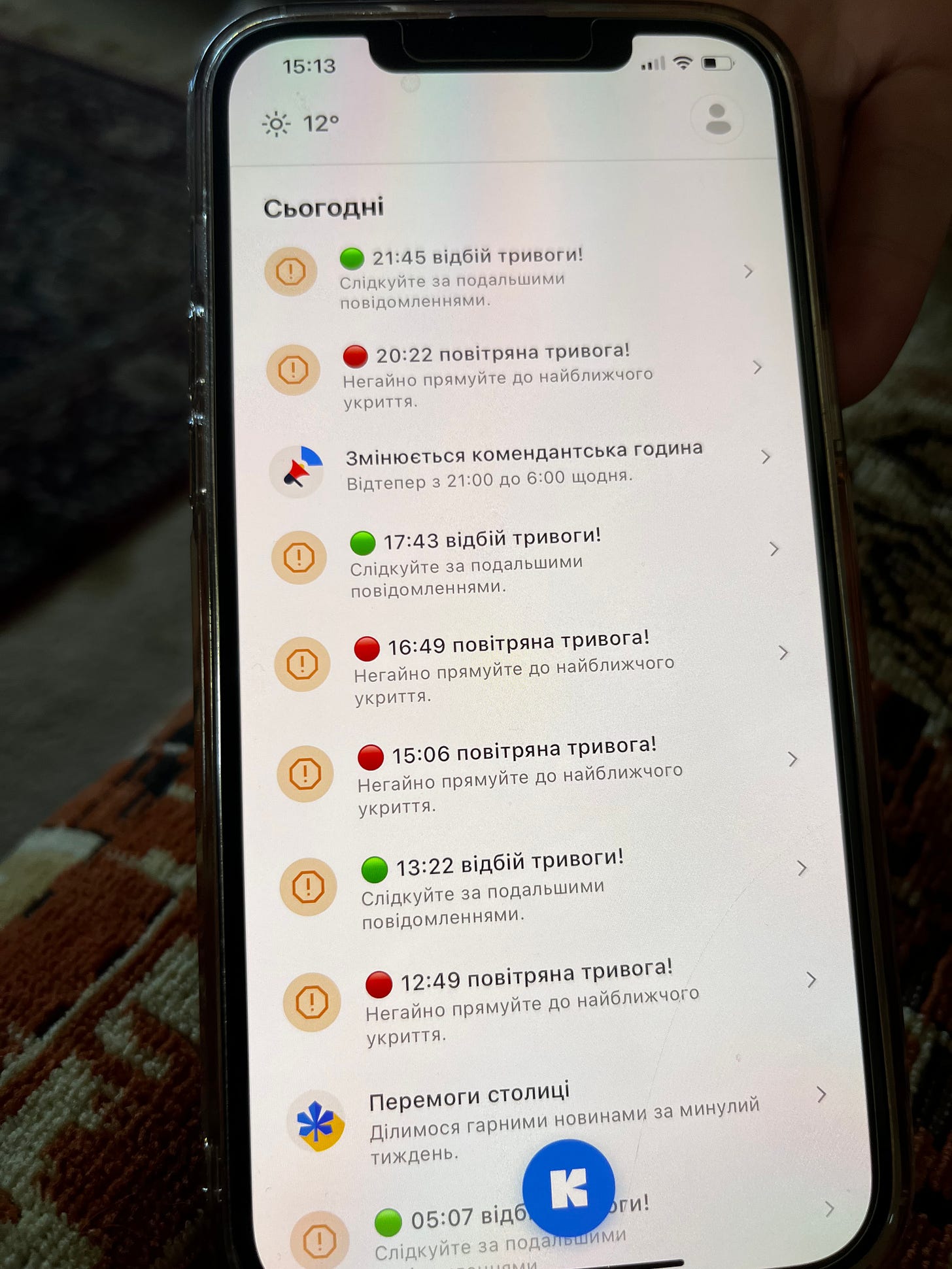

The green dots on the phone app mean it’s OK to go out. The red dots mean to hide away from another potential Russian shelling. When the red dots come on, several times a day, her phone lets her know the sirens are about to go off.

“People live with this all the day,” Vasylenko said. “We lived with this all day. The siren, it’s very awful. I don’t know how people can do it, but this is what life has become.”

A little over three weeks ago, Vasylenko and her children, Glebe, 12, and Solomia, 7, said goodbye to her husband, Kostyantyn Semchynskyy, a political science professor at a university in Kyiv who joined others to defend Ukraine from Russian tanks and troops. The journey with a flood of other refugees escaping war took them across Ukraine to Poland, eventually to Austin, Texas, and then to West Lafayette, to the home of her mother-in-law, Nataliya Semchynska.

Five weeks of fear, Vasylenko said, have made her feel 10 years older.

Her children are secure, seven time zones removed from the sirens, the shelling and the shooting. “That’s what I should do for them, like a mother,” Vasylenko said. Each night so far in Indiana, at midnight, she’s called her own mom. That puts the call at 7 a.m. in Brovany, her mother’s town, less than 20 miles from Kyiv.

“Bombs are around her house every day,” Vasylenko said. “It’s awful to call your mother and see how she’s crying. … I feel very bad being comfortable here. Family is there. Friends are there. Life is there. Your life is like on mute. I just want home.”

The story about how Vasylenko and her children made it to West Lafayette starts with the first missiles fired by the Russians on Feb. 24. One hit close enough at 5 a.m. that day to shake their apartment building in downtown Kyiv.

A day earlier, she’d been holding school for 30 kindergarten-age children in the Montessori program she runs there. She said few believed Russian President Vladimir Putin would actually invade, after amassing troops near the Ukrainian border.

On that first morning, Vasylenko said she contacted parents of children at the school to tell them not to come that day. The second day, after a bomb hit a building two streets away, she said she gathered documents for the school, packed some clothes and went to a summer home the family has near Kyiv, where Semchynskyy had been staying.

From there, she and other mothers and their children – a company of 15 – banded together with the hope of traveling together to the western border of Ukraine, as their husbands, brothers and others prepared to defend the country.

Each day, they said farewells. Each day, they ran into obstacles. A column of Russian tanks one day. Ukrainian soldiers warning about Russian bombs and mines another. It went on like that for 10 days, she said.

“Every day, it was like you say goodbye to your house and go to find some way, but you don’t know which way you have to go and what you need to take with yourself,” Vasylenko said.

They tried to get used to the sounds of the bombs from morning until evening. She said she was scared enough that she barely ate. The summer house had a cellar that could fit four people, if they stretched out. Or they would sleep on the floor. She said it was time to get out.

Vasylenko said she and the children took backpacks, shoes for hiking, a laptop, water, food and a warm change of clothes, gathered with the group of women and children they knew and struck out.

“Just any way,” Vasylenko said. “If not this way, that way. We knew we should just find a way.”

She said they couldn’t trust green corridors – routes for people fleeing and for humanitarian aid – because they’d heard reports of Russians killing civilians. They wound up finding spots on trains to Lviv, a city in western Ukraine, and then in cars with drivers who tried to get them close to border crossings, only to turn back and tell them they’d be better off walking the final kilometers rather than waiting in traffic queues that wouldn’t budge.

Vasylenko said they walked along roads and took short cuts through fields for the final leg to the border of Poland, losing communication with family as another air raid siren went off. She said they pushed on, knowing the only other option was to lie on the ground and wait.

“I didn’t hear from them for seven hours,” Semchynska said. “I was just going crazy.”

The border crossing turned into 12 hours of standing, waiting and moving a few feet forward at a time in frigid conditions. Finally in Poland, they stayed in a gym, found a change of clothes and were invited to the homes of volunteers welcoming them. They made their way to Warsaw. They split with their traveling party, each family making plans to stay with someone in Prague, in France or – in their case, because airline tickets were waiting – family in West Lafayette.

Here, in the home of Semchynska and retired Purdue professor Joe Uhl, Vasylenko enrolled Glebe in West Lafayette Jr./Sr. High School. (The report: “Pretty good first day,” Glebe said Monday.) Solomia would be enrolled soon.

“Some kind of normal life,” Vasylenko said.

How long a normal life would be in Indiana, Vasylenko didn’t venture a guess. She said she was hoping Western nations would help arm Ukrainian military to defend the country. She said that as long as Russian forces targeted civilians rather than confronting Ukrainian soldiers, she considered it “not a war, but genocide.”

She checks her phone and shows the dots tracking air raid sirens in her home town. They’ve just turned red.

“I want to be in a safe place,” Vasylenko said. “And this is a safe place. But it’s not where we belong. I just want to go home. To our home. How long it will be this way, I don’t know.”

In other coverage …

Thanks to the Center for C-SPAN Scholarship & Engagement for sponsoring today’s edition. On Wednesday, April 6, Lafayette native and C-SPAN founder Brian Lamb will host Harold Holzer, author of “The Presidents vs. the Press: The Endless Battle Between the White House and the Media – from Founding Fathers to Fake News.” See more details below.

DEAL ALERT, TIME RUNNING OUT: Thanks for signing up and making the reporting project work. Not a subscriber, but thinking about it? Now’s the time: Through the end of March, monthly and annual subscriptions are 10% off. I’ll do my best to make it worthwhile.

Have a story idea for upcoming editions? Send them to me: davebangert1@gmail.com. For news during the day, follow on Twitter: @davebangert.