Purdue groundwater expert on LEAP pipeline: ‘I’m very skeptical.' A Q&A

IEDC promises to let university researchers review a study aimed at taking Tippecanoe Co. water. Purdue prof Marty Frisbee tells what it will take for the science to tell him any of it makes sense

Support today comes from Purdue’s Office of Diversity, Inclusion and Belonging, presenting the Dance Theatre of Harlem, Jan. 16, at Elliott Hall of Music, in a 2024 Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. commemorative event. Powered by Purdue Convocations. For free tickets and group orders, check the details below.

PURDUE GROUNDWATER EXPERT ON LEAP PIPELINE: ‘I’M VERY SKEPTICAL’

At a time in Tippecanoe County when groundwater has become the stuff of grocery aisle conversations, the line to Marty Frisbee’s door at Purdue has been steady with layman questions about a topic in his groundwater/surface-water interactions wheelhouse.

“People just want to know – what do you think?” Frisbee, an associate professor of hydrogeology and applied geology, said. “And it’s understandable. There’s a lot at stake here, for all of us.”

At stake is an Indiana Economic Development Corp. plan to pump tens of millions of gallons from Wabash River aquifers in western Tippecanoe County and send it via a pipeline – reported cost: $2 billion – more than 35 miles away to developments dreamed of in the 9,000-acre LEAP district in water-starved Boone County.

The pushback around here has been substantial. And growing.

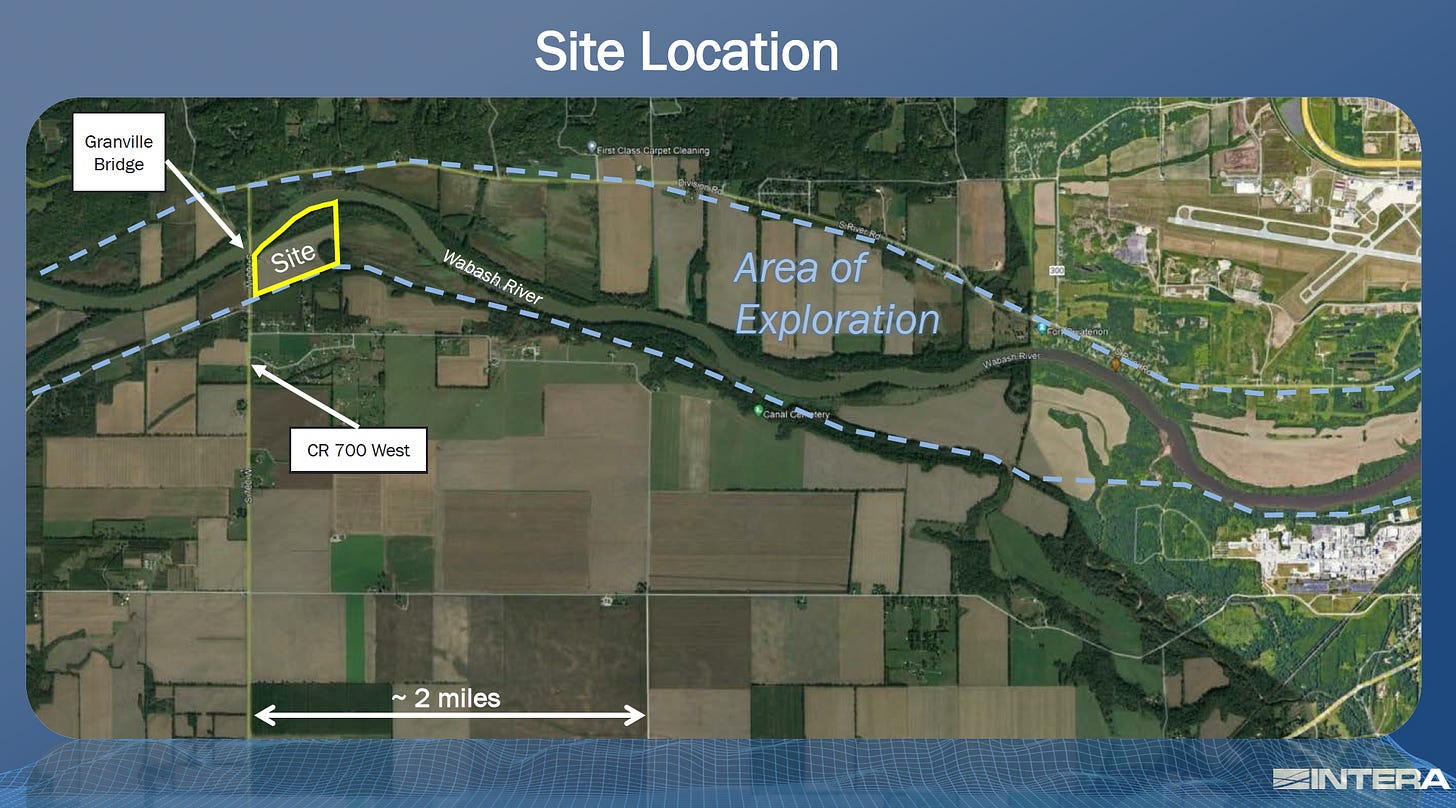

This week, INTERA, a Texas-based and IEDC-funded consulting firm, is expected to run a second set of well tests at a site west of Granville Bridge, about seven miles downstream from Lafayette. The first round of tests had INTERA and the IEDC touting wells that could pump upwards of 45 million gallons a day without hurting the aquifer in Tippecanoe County. The IEDC has promised to let researchers at Purdue, IU and Ohio State review the study’s findings when they’re done in early 2024.

Frisbee said he and other groundwater researchers are still waiting on more of the data to verify INTERA’s conclusions and IEDC’s assumptions. Frisbee said that recently Jack Wittman, INTERA vice president and hydrologist, reached out and wanted to sit down and chat about some of the modeling going into the LEAP pipeline study.

Going in, Frisbee said he has serious doubts about a plan that could take as much as 100 million gallons a day from the Wabash River watershed.

Here, Frisbee talks about the LEAP pipeline concept, the shock he felt when he first heard those numbers tossed around and what it will take for the science to tell him any of it makes sense.

(The Q&A has been lightly edited for length and clarity.)

Question: You were part of the League of Women Voters forum in June, when people were just starting to figure out what was happening with LEAP and Tippecanoe County water. During the whole pipeline conversation in the past year or so, I’ve thought of the issue sort of like a ski resort, with people coming at it like they would the slopes – green slopes for the very basic questions and moving up to the blue slopes as they looked for more specifics and then the black diamonds for those who are further along and into some of the advanced nuances and the activism. I thought that League forum was a great primer, one that would get you to blue intermediate slopes, at least, to at least understand what the initial stakes are. Seems like we’ve learned a lot since then.

Marty Frisbee: It seems like we're constantly learning more as this progresses. I was asked to give kind of a primer on groundwater. I thought that it would be better to look back on some of the various questions that I get from the community when I do public outreach and just focus on those questions. What is groundwater? Where does it come from? Those sorts of questions. Like you said, that's kind of a first level to the topic. You're trying to learn the basics, so that you can get to the point where you understand some of the more complex processes.

Question: A lot has happened or come to light since then. What have you learned since that June meeting? What do you see happening?

Marty Frisbee: One of the good things that's potentially come out of this is you see the public being engaged in groundwater like I don't think they ever have been before. I've talked to (Tippecanoe County Commissioner) Tom Murtaugh about this. Tom has said that this topic has gathered more public interest than any other topic that he remembered. From my perspective, it's good to see people that are engaged and concerned about their water, because groundwater is an extremely finite resource. It's been encouraging to see the community pull together. They have questions. And I've had people come to my office, even, which is not something that happened before.

There's been a lot of public outcry, wanting more transparency about what's going on. You know, (retired Purdue professor and geohydrologist) John Cushman and I both have asked to see some of the modeling framework, and Jack Wittman, I believe, wants to do that – which would be good. We really need to see some of the model. At first it was a problem – they weren't sharing any data. And the data, by itself, is one thing. John and I both are trained hydrogeologists. We could look at the data and see what the data tells us. But the second part is to actually see how the consulting team arrived at some of the model results that they came up with. That's really important for us. We really need to know the ins and outs of the model to understand where the data come from, so that we can make a critical assessment and inform people in the community about, say, what are some of the limitations of the model? What's the model doing correctly? That's the scientific approach. It's a nonbiased approach.

Question: Do you know or have a sense about any of that right now? If you had to look at it from the outside, can you say, legitimately, yeah, this is a bad model, this is a good model, or it’s something in between? Or, knowing what you know, is that just out of your realm right now?

Marty Frisbee: I want to sit down and talk to Jack Wittman first and hear what he has to say about some of the model structure. I have forwarded along my interpretations and things that I think that I would like to see from the model. For me, it's too early to say whether it's a bad model or a good model. I really need to see the modeling structure before I make that level of assessment.

There are certain things in the data that did concern me. First, there's been this recent debate, back and forth between the mayor of Lebanon and the IEDC about this 100 million gallon per day number, right? I was at a meeting back in March where they used this number. This number did not just appear out of the blue.

This number was provided during the meeting. … Jack Wittman was present. There was someone from the IEDC present. They told that this could be as much as 100 million gallons per day. So that number just didn't magically appear. That number was under consideration. Whenever I heard that number, at the very beginning of all of this, that number shocked me, because that's a lot of water. That's a massive amount of water.

Today’s a good day to subscribe to Based in Lafayette reporting project. Free and full-ride subscription are available here.

Question: Is there a number that would not have shocked you? If they said, We're going to pull what Lafayette pulls in an average day, about 11 million gallons a day, 17 million gallons a day during peak season, would that number have shocked you, too?

Marty Frisbee: That number may not have shocked me. But the only reason that it wouldn't have shocked me is that, of the data that we have available, I think the maximum pumping rates are somewhere in the mid- to upper-20 million gallons per day. So like 27, maybe 26 million gallons per day – and that was during the drought. So the system was being stressed. Something around that range would have caught my attention. But 100 million gallons caught me off guard, because that's a massive amount of water.

Question: Can you put it into perspective. I mean, comparing it to what all of Lafayette uses in a day isn’t a bad start. But how do you tell people when you contemplate 100 million gallons a day?

Marty Frisbee: I ask people if they know what “one acre foot” means. That's a volume of water that we commonly refer to in hydrogeology. One acre foot means you have one acre of land that's flooded to a depth of one foot. Imagine that you're at the football stadium. Without the end zone, it's about an acre. And so if you fill that to a depth of one foot, that is 326,000 gallons. Now think about how deep you would have to flood the field to get 1 million gallons – that’s essentially about three feet of water to pump out 1 million gallons per day. To pump out 10 million gallons, that’s a football field flooded to 30 feet. To get to 100 million gallons, you’ve got to flood it over 300 feet. … That’s taller than all the buildings in West Lafayette.

(Editor’s note: For context, The Rise apartment complex on State Street was listed at 168 feet from the sidewalk when it applied for FAA clearance for maximum height. So, using Frisbee’s analogy, 100 million gallons is roughly the Ross-Ade field, goal line to goal line, filled to twice the size of one of the tallest buildings in the city. Or another way: Water filling a rectangle box, a football field long by a football field tall.)

That’s what they want to pump out every day as an upper number. I’m very skeptical, put it that way, that they’ll get there.

Question: What are some of the concerns you’ve passed along to state lawmakers?

Marty Frisbee: To get back to your framework here, if we start at an entry- to mid-level answer to your question, every aquifer has specific hydraulic properties and the differences in hydraulic properties in geology dictate which types of models that we should use for different aquifers. So you can't use just one model for every aquifer.

Question: So, maybe the difference between hitting a home run in Wrigley Field vs. hitting one in Fenway Park, if you’re a baseball fan?

Marty Frisbee: Yeah, without the Green Monster there, it’s a different ballfield. … Out west, a substantial amount of the water comes from what we call confined aquifers. These are aquifers that are found between confining layers of rock. Here, what we have is an unconfined aquifer, meaning that there's nothing sitting on top of it and it's in direct communication with a river. It's a very unique situation as far as aquifers go. I know that's getting a little bit above the entry level, but does that make sense?

Question: The funny thing is, you're probably speaking to more people than you think at this point, with people ramping themselves up in what aquifer means. Does that mean that the Wabash River feeds this aquifer and helps it recharge?

Marty Frisbee: There are good questions about recharge. First and foremost, recharge occurs when water infiltrates through sediment and actually makes it to the saturated sediment – the saturated sediment typically defines where groundwater occurs. The aquifers that the IEDC are interested in are called alluvial aquifers.

These types of aquifers are in nearly constant communication with a river. You have alluvial aquifers out west, say, in New Mexico and Arizona, that may only get recharged during the monsoon season or during the snowmelt season. But here we have perennial streams, so these the rivers here are in constant communication with these alluvial aquifers. The exchange rates though – and this is getting back to your original question – we do not know much, if anything, about the exchange rates between the alluvial aquifers and the Wabash itself. That's a big unknown. And that's one of the concerns that I passed along to (state Sen. Spencer) Deery. We can try to understand those from Jack's model. But we really do not have any direct assessment of those exchange rates.

Question: When you say exchange rates, does that mean that the Wabash is flowing by at whatever millions or billions of gallons a day, you don't know how much of that goes back down into the aquifer on a daily basis? Is that what you’re saying?

Marty Frisbee: Yes. The point where the river interacts with those sediments, it's like a revolving door at a hotel, for example, if you're looking for an analogy. There's water that enters the river, and there's water that leaves the river. So, it's a two-way exchange of water between the alluvial aquifer and the river itself. During the summertime, when the rivers are starting to get really, really low, there may be a change in those exchange rates. There may be a case where there's maybe less water coming from the river to the aquifer. It just really depends on the situation at hand.

Question: But you don’t know much about how that actually works, correct? That seemed to be your point in June (at the League forum). And I hear that now.

Marty Frisbee: Yeah, that's one of the big concerns, too, is moving to an uncertain future with respect to climate change. We're expecting the summers to perhaps get drier and hotter. The river baseline levels could decrease. So, those exchange rates are critical whenever you're pumping, say, 40 million gallons per day, you really need to understand what's going to happen to the river 20, 30, 40 years from now. Because it's not a stationary target.

Question: Do you have faith that, say, maybe the consultants understand this? But IEDC officials, when they went to ask for $122 million to get the 1,000 acres in Boone County to hopefully land a $50 billion semiconductor plant, told the (Indiana State Budget Committee) that as long as we have water in the Great Lakes, the Wabash River will be OK. That's a pretty big misunderstanding of the situation. Does that seem to feed your concerns?

(A note for context: Here's a clip from the June 22, 2023, Indiana State Budget Committee hearing, when state Rep. Gregory Porter, concerned about the speculative nature of the extra land purchase for the LEAP district, asked about where the IEDC thought it would get water for a semiconductor plant. David Rosenberg, then the IEDC’s chief operating officer and now Indiana secretary of commerce, tried to dispell those doubts, telling state lawmakers: “We’ve started engineering and design studies on the potential to bring water from the Wabash alluvial aquifer, which is replenished by the Great Lakes, so as long as there’s water in the Great Lakes, there will be water in this aquifer.” The committee approved the $122 million, with some lawmakers praising the IEDC for moved “at the speed of business.”

Marty Frisbee: I think you're being kind to that statement. I think it's a blatant lie. I don't think it's lack of hydrologic knowledge, which most certainly the people at the IEDC and the mayor of Lebanon have not shown any degree of hydrologic sensibility. But I think it's a blatant lie on their behalf to somehow connect the Wabash and the alluvial aquifers to the Great Lakes. We expressed this concern to (Sen. Deery), also. I don't know where this thought came from. But it's not true.

The aquifer itself is recharged by probably two things – it’s recharged by some water that's leaving the river, and it's recharged by some water that's flowing through the ground that's on its way to the river. So, there's water moving through the aquifer. From some of our research, when we look at these aquifers around here, we see an isotopic signal – these are isotopes that we measure in water – that shows that these aquifers are being primarily recharged during winter and spring, sometime between fall and spring. Because the isotopic signature kind of matches that time of the year. There's some amount of water that's entering the aquifer from the river, and there's some amount that's just the natural groundwater recharge. It's not connected to the Great Lakes.

Question: That seemed to be something said that went over the heads of budget makers at the state.

Marty Frisbee: I was actually shocked when I heard that statement for the first time, when someone showed me the evidence for this. Because there's a general lack of hydrologic knowledge, which is OK. We work in a specialized field. For me, public outreach is important. All of my graduate students, each graduate student in my research group, will do one public outreach event before they are able to defend (their dissertation), because I feel like we have to be able to tell the public why our science matters. So, lack of hydrologic knowledge is nothing to be ashamed of. But lying about how hydrology works is a totally different thing. And that's what this feels like, to me. This feels like you're lying to get money. It didn't feel appropriate.

I don't think that the common person around here, even if they're not knowledgeable about how the hydrologic system works, would draw a connection between the Wabash and the Great Lakes. The only way that you could do that would be maybe if you went back in time and reinvested in the Wabash Erie Canal, that was a connection to Lake Erie. Maybe they were trying to say that the processes which feed the Great Lakes also feed the Wabash? But that’s being generous. … It’s a gross representation, to be polite.

Question: What other issues have you brought to lawmakers who’ve asked?

Marty Frisbee: My concerns were mostly focused on the hydraulics of the aquifers – how these aquifers work. I was concerned with what's going to happen at baseflow during these really dry summers, when the river’s very thin. What's going to happen when you have a pumping center that's combined pumping over 40 million gallons per day? What's going to happen to the river at that point? This should be a question that downstream users should be asking, because it has direct implications for water sustainability, and they're part of the system.

The other thing I’m concerned about is that INTERA did pumping tests – I think they were pumping roughly about 2 million gallons per day (this summer). They were showing the drawdown for that, and then they took the hydraulic parameters that they were able to obtain from the pumping test and put those into a model. The model itself shows some pretty significant drawdown around the wells and it propagates change in head, or drawdown, about a mile away from the wells, it looks like. I was kind of puzzled that if you have a water that has a high transmissivity – transmissivity means the ability to transmit water, essentially – why do you have such a steep drawdown around the well, and you're still claiming that the river is replenishing the water as soon as it's being pumped. That's one thing that I want to talk with Jack (Wittman) about, is to get more details on how that interpretation was made.

Question: There have been neighbors who have come forward and said they had gravel in their water system and that they got some sulfur smell they couldn't explain until they found out that testing had happened in July. As INTERA is getting ready to pump on a nearby second site, they’re using canning jars to collect water from their homes and changing whole house filters now, so they can monitor what happens over the next week or so. Were you surprised that there were problems? Or do you think those problems might have been something else?

Marty Frisbee: Unfortunately, I haven't talked to these people. So, I don't know the whole story there. But as far as the smell goes, there are ways that the smell could be related to disturbing some of the clay-rich sediments that are present. I've actually encountered this myself, when we install little, what we call piezometers – which are like miniature wells – out in the Ross Hills area to do some research. When you hammer down through some of those clay layers, they smell really sulfur rich. You also have in the glacial sediment itself, you can find pyrite, fool's gold. Pyrite is an iron sulfide mineral, so when it weathers it releases iron and it releases sulfur, so you can get a sulfur smell. Long story short, there could be a geological explanation for the sulfur smell. That part didn't surprise me as much as the sediment part.

John Cushman and I've been discussing different ways that the sediment could get there, because I would assume – and I haven't seen any of their well logs or well construction information for the residents there – but I would assume that they're well would have had a screen on it, especially if it's in a sand and gravel top aquifer. That would prevent some of the sediment from coming in. I'm still kind of curious as to how sediment got into the well. That's something I need to follow up on. And I would love to talk to the people. If they have samples of sediment that they could show me or we could come out and look at them, you know, that would be great. That way I can get a better understanding of what actually happened.

Question: I spoke to Jack Wittman in September, along with an IEDC official, just after the initial test well report came out. They insisted this is not a done deal. Secretary of Commerce David Rosenberg has been saying similar things about the need for the pipeline, even as tests continue. But results in the initial report seemed confident that there was enough water in the aquifer to confirm the concept. Is there a way that this comes out that there really is 100 million gallons that can be pumped every day – or let's say half of that amount – and Lafayette, West Lafayette and Tippecanoe County are still protected? Is there a way that happens?

Marty Frisbee: That's a tough question to answer. With the data that I have now, I would err on the side of caution and say that I doubt that there's any single well that's going to give you 100 million gallons per day. I'm very skeptical about the 40 to 50 million gallons per day. I know that the Ranney wells (radial collector wells) can provide a lot of water. But I'm erring on the side of caution, because our highest data points are again around 27 million gallons a day. And that was for a short period of time. Even during that short drought, there was some associated change in drawdown in the aquifer with that.

Question: In the Granville area, neighbors are frustrated that the next test is coming in December, when there’s no irrigation happening, uses are low even in gardens. Is there a way to do a stress test, during irrigation season in the fields in the summer, that would prove one way or another whether the IEDC’s plan might work?

Marty Frisbee: I think it would be better if you want to gain the public’s confidence to run some of these tests during the growing season, when water demand is higher. … I think it would have to be coordinated somehow through some extension agent, so that local residents would know what you're doing, I think it may be a good way to test your aquifer. (INTERA’s) current wells and the current pumps may not be capable of that rate. I'm not sure what the specs are on some of the hardware that they have installed in the wells, either. But there could be ways to run a stress test for two or three days or a week and see what the cumulative effects are. That may be a good way to test your model, too – to test it whenever the folks are trying to irrigate and/or the river is at the low stage.

Question: You talked about wanting to see what the modeling is. Do you have suspicions that the modeling is geared to affirm the assumptions of the IEDC?

Marty Frisbee: I'm not going to say anything negative about Jack (Wittman). I worked in consulting, too, and I still like to help with consulting projects from time to time. And when I worked in consulting, we did not give the client the answer the client wanted. We gave them the answer the science gave us. I'm hoping that's what Jack's doing. That would be my best answer. I'm not going to say anything negative about Jack. I just don't have the data to assess his model at the moment. Hopefully, we can sit down and the two of us can chat about the model in the coming January or February timeframe. Then I’ll have a better understanding of what his model actually does.

Question: The IEDC says it has a team of people at Purdue, IU and Ohio State who are standing by who want to look at this and review the results. Are you part of that? Or are you off to the sidelines of that?

Marty Frisbee: I was asked to review. I haven't seen anything, yet. But I was asked to review. And I would be happy to do that.

Question: There are persistent questions about that, with assumptions in the community about the IEDC paying for a study for a solution to an IEDC project and vetting the results with people the IEDC chose. County commissioners, for example, have been asking for an outside review from someone totally unbiased. There’s a thought: Who do we trust at this moment?

Marty Frisbee: I've felt and heard some of those similar concerns in my own neighborhood about some growing distrust. But I would tell them the same thing I tell my neighbors: I'm not employed by the IEDC. I’m a scientist, first and foremost. So, you have to be objective, you have to be able to also take criticism. And the IEDC has made statements that they don't understand why the public doesn't trust them. You know, this is science. It's not about trust; it's not about faith. It's about seeing the data and seeing the actual numbers – what do the numbers say? I think we've got to make that clear to the public. We want to see the data as much as they do. We want to see how the data is being interpreted as much as they do. And we have to remain objective in that part.

Question: What questions are people coming with when they knock on your office door? What do they ask?

Marty Frisbee: Is this too much water? Is this going to affect the river? Is there any way to stop it? Is there any way to slow this down? Is there any way to encourage them to look elsewhere for water? It's all of these questions. They're the same questions from everyone. Like I said, it's good. It's good that people are engaged, and they’re concerned about their water. But there's also a lot of misinformation out there, too.

Question: When you’re asked if there’s any way to stop this or slow it down, what answer do you give?

Marty Frisbee: I’ll tell them it's difficult. There's no groundwater protection policies, or not many that I'm aware of, that can stop this. I know, locally, there have been some moratoriums. It seems like the IEDC and higher up are kind of scoffing at that. So, I don't know what effect they'll have. They may have an effect on slowing it down, but I don't know that they'll stop it. I don't know. I don't know what to do. I don't know if there is a good way to stop it, unless they find another resource that is less contentious. That would be the only way. It seems like they have money invested in this.

WATER TESTING, ONGOING

Results from the IEDC’s $2.9 million study of the Wabash River aquifer are expected from Texas-based consultant INTERA in January 2024. County commissioners have been told that pumping wouldn’t start until the week of Dec. 11 at a second test site. Testing at the second site, on acreage along County Road 75 South, about a mile-and-a-half southwest of Granville Bridge on County Road 700 West, is expected to start sometime this week.

The IEDC released preliminary test results in September, based on pumping done in early July on a 70-acre site just southeast of Granville Bridge. Using 12-inch diameter test wells pumping at a constant rate for 72 hours, INTERA pumped a couple of millions of gallons a day, measured the drawdown and extrapolated the potential with modeled results. Based on those tests, according to an IEDC executive summary, two wells on that site could produce a combined 30 million gallons a day, with model scenarios that “suggest much higher pumping rates can be sustained” with “the upper bound … not yet defined.” During a community meeting a week later, Jack Wittmann – a hydrologist and vice president of INTERA – said the tests suggested that up to 45 million gallons a day could come from two high-capacity radial collector wells on that site.

In November, Gov. Eric Holcomb reassigned an ongoing study into the size and capacity of the Wabash River aquifer, taking it away from the IEDC and handing it to the Indiana Finance Authority to review and finish. That’s expected to be done in January 2024. Indiana Finance Authority officials also were charged with conducting a regional water study in Tippecanoe County and 12 other counties, by fall 2024.

A TIPPECANOE COUNTY MORATORIUM

Tippecanoe County commissioners unanimously finalized an ordinance in November meant to slow the pipeline plan. The ordinance does a couple of things:

It puts a nine-month moratorium on exporting “high volumes of water” – defined in the measure as 5 million gallons a day – outside Tippecanoe County.

It also would put a similar nine-month moratorium on installation of new high-volume radial collector wells, capable of pumping more than 1 million gallons of water a day. Radial collector wells send screens out horizontally to collect water from a broader area and are part of the high-volume pumping plan being considered for the LEAP pipeline.

IEDC officials have scoffed at the county’s move as an effort to “stoke further rhetoric and misinformation” about ongoing water studies along the Wabash River, saying commissioners knew full well that no pipeline or large wells would be ready to go between now and summer 2024. Commissioners say the nine-month deadline is to push the issue through the 2024 General Assembly session and past the typical July 1 implementation date for new laws, to give lawmakers time to find a statewide answer to Tippecanoe County concerns about the IEDC’s plans. Commissioners said in November they’re prepared to extend the moratorium if the General Assembly doesn’t act.

WHERE THINGS STAND AT THE STATEHOUSE, A RECAP

In November, local lawmakers received word from House and Senate leadership that the General Assembly would not entertain any funding measure, at least in the 2024 session, for a water pipeline. State Sen. Spencer Deery, a West Lafayette Republican, said he was told that a funding bill big enough to pay for the pipeline project – local officials have been told it would be in the $2 billion price range – would not be taken up in a non-budget year.

During the legislature’s Organization Day in November, Deery also said local lawmakers received commitments that would bring “relevant stakeholders” together to come up with a bill that would “establish the basic guardrails that will help protect all communities against potential harms of large water transfers.”

FOR OTHER RECENT COVERAGE OF THE LEAP PIPELINE

Thanks, again, to Purdue’s Office of Diversity, Inclusion and Belonging, presenting the Dance Theatre of Harlem, Jan. 16, at Elliott Hall of Music. Get tickets here.

Thank you for supporting Based in Lafayette, an independent, local reporting project. Free and full-ride subscription options are ready for you here.

Tips, story ideas? I’m at davebangert1@gmail.com.

Again, watch the movie "There Will Be Blood." Hold for the milkshake scene. There's lots of terrific reporting via the Q&A format here. I appreciate the note about how hydrology conditions differ from place to place. I also think it's crucial, here, to note that we cannot control at what rate the aquifer is replenished, if at all. We can't even predict it. The only thing we can control is how much we remove. If the extraction is related to development, the simple answer is, as learned in California and Arizona, don't make a deal with the water devil. Don't allow water-hungry development in places without enough water. We don't produce water. We cross our fingers and hope it's there when we need it.

Appreciate Prof Frisbee using "lie" and "lying" about lies and lying.